One year of connecting science, people, and policy for Arctic justice and global climate

Dr. Sue Natali and Permafrost Pathways Tribal liaison for the Alaska Native village of Nunapicuaq Morris Alexie in Nunapicuaq, Alaska.

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Sue Natali Ph.D.Arctic Program Director and Senior Scientist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Brendan Rogers Ph.D.Associate Scientist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Melissa Shapiro J.D.Arctic Policy Lead, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost Pathways turns one, celebrating a year of substantial progress advancing equitable solutions to the impacts of permafrost thaw

One year ago today, Woodwell Climate Research Center’s Dr. Sue Natali gave a powerful talk at TED2022 in Vancouver to introduce Permafrost Pathways—a collaborative new effort between Woodwell Climate Research Center, the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), the Alaska Institute for Justice (AIJ), and the Alaska Native Science Commission (ANSC) connecting science, people, and policy for Arctic justice and global climate.

Video: Dr. Sue Natali introducing Permafrost Pathways at TED2022 in Vancouver.

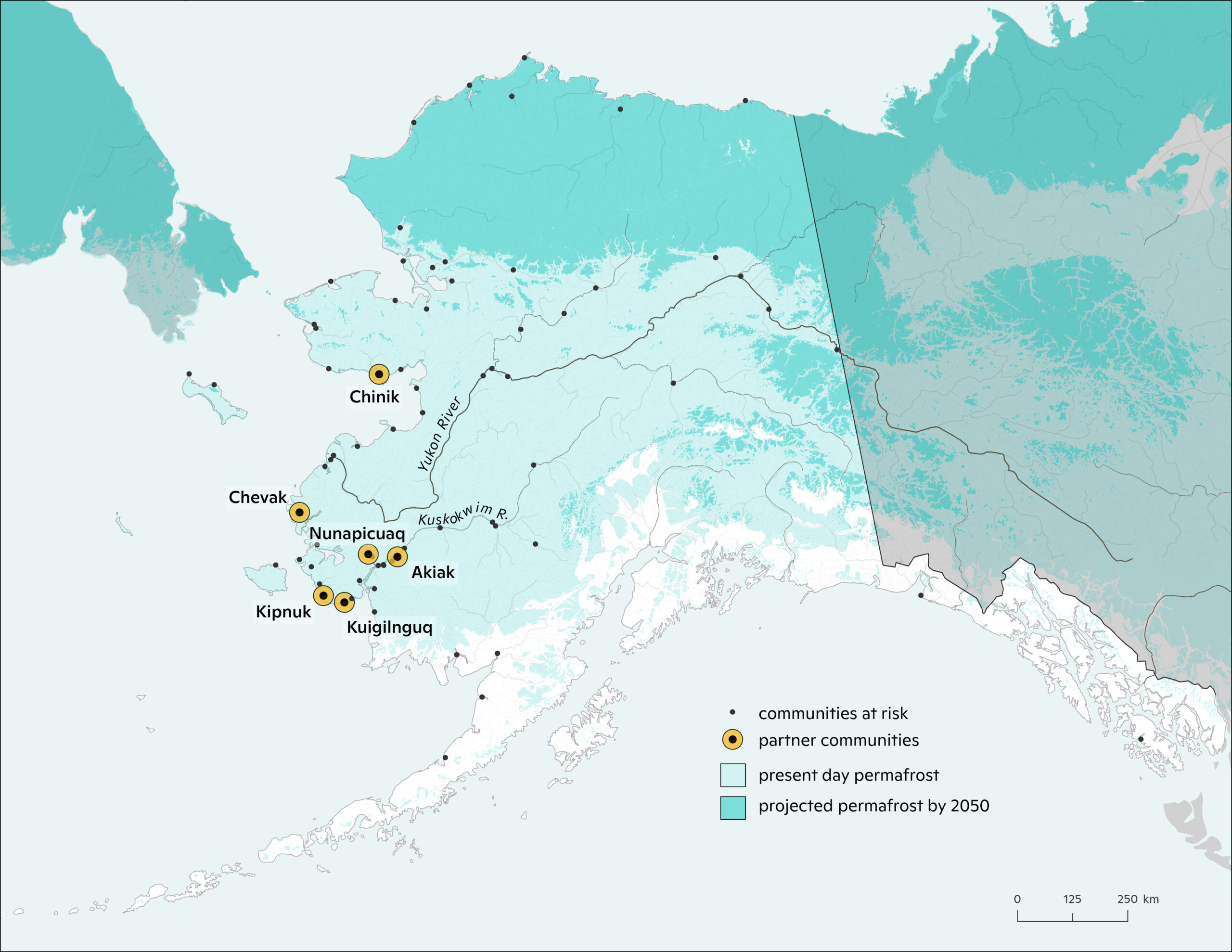

In our first year following Dr. Natali’s TED Talk, the Permafrost Pathways team began establishing an Arctic Carbon Flux Monitoring Network and has advanced Arctic modeling to better understand how thawing permafrost will impact the global climate. Working with Alaska Native communities affected by permafrost thaw and other compounding environmental hazards caused by Arctic warming, we’re also co-creating Indigenous-led climate adaptation plans and informing local and international policy to advance equitable solutions to the climate crisis in the Arctic and beyond.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Monitoring permafrost thaw and carbon emissions

An essential goal of Permafrost Pathways is to ensure that permafrost carbon emissions are accounted for in global climate policy. The first step in achieving this goal is to assess the current carbon balance of the Arctic by determining how much carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) are released into and removed from the atmosphere (referred to as carbon flux).

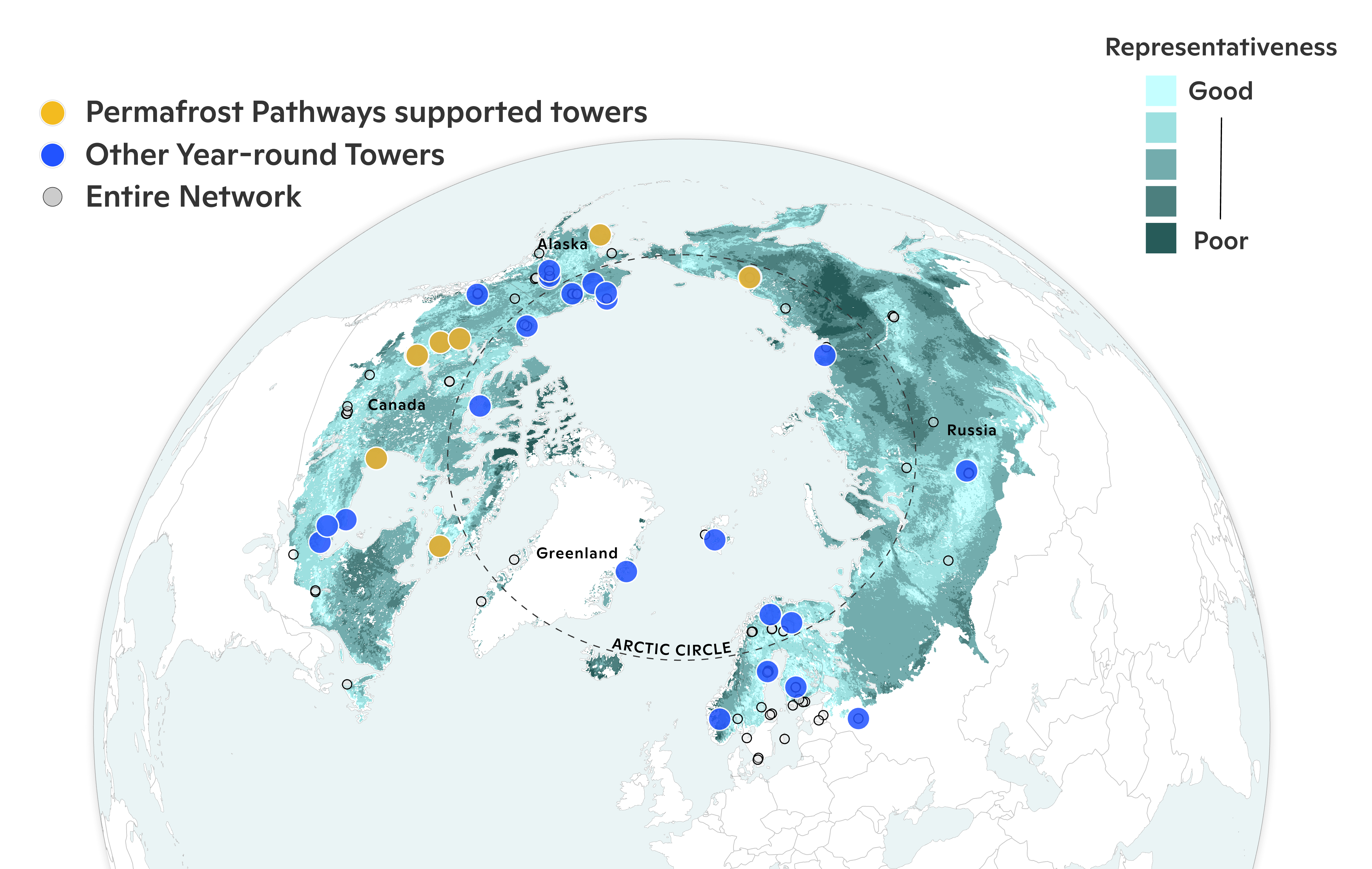

To track CO2 and CH4 fluxes, we use a method called eddy covariance, which directly measures greenhouse gasses as they move between soils, plants, and the atmosphere. Prior to Permafrost Pathways, there were only 15 locations across the Arctic where eddy covariance towers ran throughout the year and measured both CO2 and CH4. With guidance from our Arctic Carbon Flux Steering Committee—an international team of scientists who work across the permafrost region—the Permafrost Pathways carbon flux network team will install 10 new, strategically placed eddy covariance towers and support existing towers by providing equipment for year-round measurements of both CO2 and CH4.

Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Kyle Arndt and Patrick Murphy installing a new eddy covariance flux tower in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Last summer, we installed a new eddy covariance tower in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada and supported existing towers in other regions of Canada and Alaska. We also provided power and equipment to a tower in remote Siberia that was at risk of shutting down due to sanctions and lack of funding.

The new and upgraded carbon flux monitoring sites will fill a major knowledge gap in our understanding of the current and future impacts of the Arctic on the Earth’s climate. We’re combining these new data with synthesized flux data from across the permafrost region, satellite remote sensing products, and machine learning methods to extrapolate and map carbon fluxes across the permafrost region. Preliminary results indicate that northern boreal forests remain a net CO2 sink—the land is storing more CO2 than is being released into the atmosphere, but some areas of the tundra have already shifted to a net source of CO2 to the atmosphere.

Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Jackie Hung and Dr. Sue Natali working with Columbia University’s Dr. Ludda Ludwig on an eddy covariance tower in the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta in Alaska. Photo by Mitch Korolev / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Ground measurements provide much-needed observations of Arctic carbon exchange, however, there are some key processes that are not fully captured by the network but that may greatly accelerate climate change. Of particular importance are wildfire and abrupt thaw, which occur when the ice in permafrost melts and the remaining ground collapses, causing erosion and landslides.

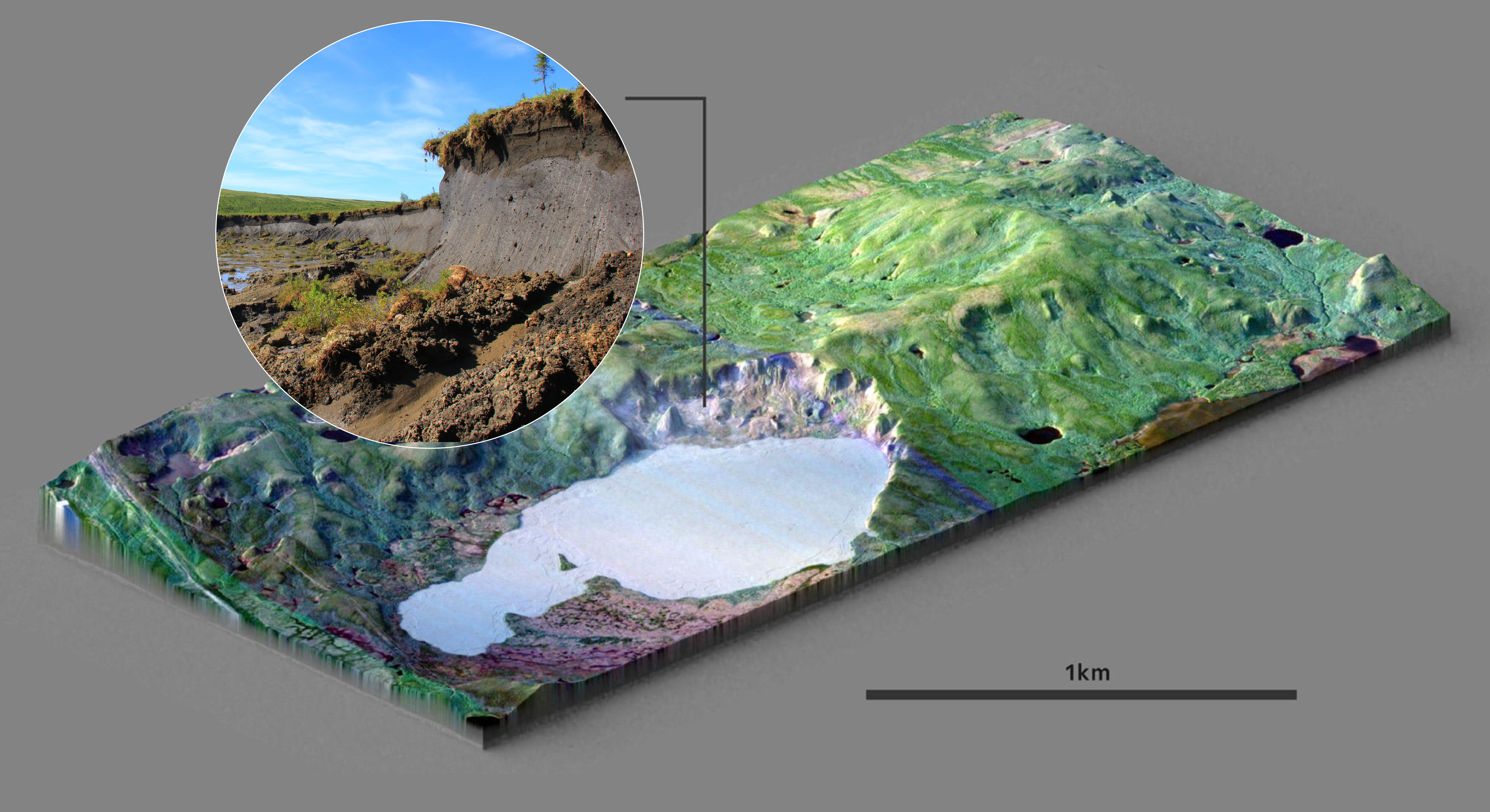

These disturbances pose a serious threat not only to local Arctic communities but also everyone on the planet because they can rapidly release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. However, there is a lack of comprehensive maps of these disturbances across the Arctic. We are using high-resolution satellite imagery and new deep learning techniques to detect thaw features and wildfire across the Arctic. Initial results are very promising, including an initial publication on retrogressive thaw slumps in Siberia. Permafrost Pathways is working on scaling our mapping to cover the entire circumpolar north.

Example of an abrupt permafrost thaw feature using high-resolution satellite and topography data. The retrogressive thaw slump is located in the Yamal Peninsula of Siberia. Image by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Developing more accurate Arctic carbon models

The fundamental reason why permafrost carbon emissions are not adequately included in future climate trajectories and remaining carbon budget estimates is that most climate models don’t include permafrost carbon. To address this, the Permafrost Pathways modeling team is focusing on developing the most advanced model of permafrost carbon and related ecosystem processes; translating permafrost carbon emissions into policy-relevant scenarios and information; and working with international Earth system modeling groups to incorporate permafrost carbon into their models. In 2022, our modeling team was focused on developing an advanced model in collaboration with researchers at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks (UAF) to address long-standing gaps in the scientific community’s ability to model permafrost carbon.

The Permafrost Pathways modeling team had five days of lectures and labs on modeling the Northern permafrost zone at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in early 2023. Photo by Christina Schaedel / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Another major barrier to incorporating permafrost carbon into climate models has been the translation of research results into policy-relevant frameworks. Because of this, we have been developing a much simpler, faster, and policy-focused model to include important permafrost processes. When accounting for these important processes—abrupt permafrost thaw, wildfire, and fire-permafrost interactions—that have been left out of models to date, the permafrost carbon feedback is roughly four times the assessments in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) recent climate report. This means that up to half of humanity’s remaining carbon budget to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius could be claimed by emissions from permafrost thaw.

Permafrost Pathways tribal liaison for the Alaska Native village of Kuigilnguq Gary Evon discussing the village’s future as sea level rises during the September 2022 adaptation workshop at Woodwell Climate Research Center. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Co-creating an Indigenous-led adaptation process

In our first year, we signed tribal agreements with six Alaska Native communities—Chinik, Chevak, Kuigilnguq, Nunapicuaq, Akiak, and Kipnuk. Permafrost Pathways tribal liaisons lead community adaptation planning, coordinate with the project team to develop relocation toolkits, and identify policy priorities to address the impacts of permafrost thaw and other climate-caused hazards in their communities.

The scientific and technical contribution to adaptation work consists of three main activities: tracking and documenting current and past rates of environmental changes; assessing environmental conditions at potential relocation sites; and assessing future rates of change.

Maps by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Tracking current and past rates of change

Community-led monitoring and observation, which is often the only on-the-ground record of climate impacts in rural Arctic communities, are critical for securing adaptation support from state and federal agencies. To facilitate documentation of current climate impacts, we developed a storm and permafrost thaw impact survey used by and developed with our tribal partners. In 2022, Kuigilnguq set up permafrost temperature monitoring and Nunapicuaq started a water sampling campaign to assess water quality from a river that the community uses for drinking and fishing that may be impacted by runoff from a garbage dump on land compromised by permafrost thaw. We have also begun to work with satellite data to assess past rates of coastal and riverine erosion and landcover changes.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Relocation site assessments

Tribal partners Kuigilnguq and Nunapicuaq have selected potential relocation sites and have been working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) to develop a work plan for impact assessments of their current community location. We are working with our tribal partners to provide relevant geospatial data to assist with relocation decision-making, and we’ll also be working with Kuigilnguq and Nunapicuaq to assess permafrost conditions and water quality at their potential relocation sites in 2023.

Video: September 2022 House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology hearing “Amplifying the Arctic: Strengthening Science to Respond to a Rapidly Changing Arctic.” Before the hearing closed, Congresswoman Haley Stevens thanked Dr. Natali for her testimony.

Permafrost Pathways sought to increase attention on permafrost thaw as part of the “best available science” considered by the U.S. government. Dr. Sue Natali testified before the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on the need to increase funding and federal government support for Arctic research. In late September 2022, Permafrost Pathways hosted a policy convening at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The convening included project partners from the Alaska Native villages of Kuigilnguq and Nunapicuaq, federal agencies, and non-profit organizations. The convening was an opportunity for invitees to learn about the project’s current activities and preliminary plans for the six-year span of Permafrost Pathways, offer their thoughts about the challenges and opportunities at the intersection of permafrost science and policy, and consider the possibilities for communication and collaboration connecting their own Arctic projects and responsibilities with the Permafrost Pathways effort.

Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Brendan Rogers presenting during Permafrost Day in the Cryosphere Pavilion at COP27. Photo by Melissa Shapiro

Building on momentum following the policy convening, Permafrost Pathways made notable progress towards our goal of ensuring that international policy negotiations on climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience better account for permafrost thaw and resulting greenhouse gas emissions. Critical to this work is ensuring that the latest permafrost science is shared in relevant venues and that it is accessible to decision-makers. In November 2022, Permafrost Pathways attended the United Nations Climate Conference (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, where we co-hosted a side event and pavilion programming to highlight permafrost thaw as part of the policy discourse. Working with Permafrost Pathways collaborators ICCI and the Bolin Centre, we co-hosted Permafrost Day at the Cryosphere Pavilion, which included programming that featured the latest permafrost science, coproduction of knowledge, climate tipping points, and intergenerational justice.

Launch event announcing the Declaration for Ambition on Melting Ice at COP27. Photo by Rachael Treharne / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Our team also leveraged the conference to strengthen relationships with government negotiators, UN human rights and scientific experts, coalitions of observers, and environmental justice organizations, including those representing Arctic Indigenous communities. An important outcome of our scientific contributions and international policy engagement through ICCI was the founding of a new high-level group, Ambition on Melting Ice (AMI), which comprises more than 20 nations that are calling for more ambitious climate action to protect ice and permafrost in the polar and mountain regions. Support for this position was ultimately reflected in the final outcome document of COP27, which included explicit references to the cryosphere in the operational text of the cover decision for the first time.

UNFCCC 2022 in Bonn, Germany. Photo by Melissa Shapiro

Increased visibility of permafrost thaw at COP27 reflected several months’ worth of contributions from our project to UNFCCC processes, including to the Global Stocktake (GST) of the Paris Agreement and to activities of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA). The Permafrost Pathways policy team advanced our advocacy positions at a poster session and press conference at SBSTA 56 (in Bonn) in June 2022. Permafrost Pathways also submitted two inputs to the GST Technical Dialogues and supported two additional inputs led by the Climate Action Network and the “Country of Permafrost” led by Stockholm University. These submissions addressed the impacts of permafrost thaw on global carbon budgets, and the economic and non-economic “loss and damage” experienced by communities across the Arctic due to permafrost thaw and other climate hazards.

A devastated subsistence fish camp in Nome, Alaska after Typhoon Merbok. Photo by Jeremy Edwards / FEMA

Permafrost thaw integrated into key federal and international disaster policies and establishment of climate relocation governance framework

Following discussions at the policy convening, members of the Permafrost Pathways adaptation team met with representatives from several federal departments and agencies to start developing guidelines for relocation site assessments, which currently don’t exist. This year, our team will continue to work with these agencies to develop guidelines, and coordinate with U.S. ACE to assess ground conditions at potential relocation sites and identify criteria for relocation site selection.

Inundation after Typhoon Merbok in the Inupiat village of Golovin, Alaska. Photo by Ian Gray / U.S. Coast Guard

In addition to creating relocation guidelines, another key policy objective of Permafrost Pathways is to integrate permafrost thaw into U.S. federal disaster response policies that lack support for ‘slow onset’ events—like permafrost thaw—however, we also recognize the need to ensure that federal disaster response is accessible to communities in need. The impact of Typhoon Merbok on western Alaska in September 2022 and the ineffective government response to rural Alaskan communities, particularly in regard to federally-mandated language accessibility for FEMA documents, highlighted the dire need for just and equitable climate adaptation and disaster planning. Project partners at AIJ led advocacy efforts to ensure that FEMA translated critical disaster relief information, and following the egregious errors in FEMA’s translated documents, AIJ worked with Yup‘ik and Inupiaq interpreters and translators to rectify this issue with plans to expand on this work in 2023.

Video: Permafrost Pathways virtual panel Q&A in June 2022.

Publications and media highlights

Following the project launch in April 2022, Permafrost Pathways hosted a virtual panel Q&A introducing the project and providing public audiences an opportunity to engage with project leads from Woodwell Climate, HKS, AIJ, and ANSC. Ahead of COP27, Woodwell Climate launched a free online course in October that aims to educate participants about permafrost science, policy, and Arctic justice.

Throughout the year, several members of the Permafrost Pathways team have been co-authors on 18 new scientific papers in prestigious publications including Frontiers in Environmental Science, Nature Climate Change, NYU Review of Law and Social Change, and Environmental Research Letters and featured in media outlets including the New York Times, Alaska Public Media, Reuters, CNN, The Economist, and Time Magazine.

Media roundup:

New York Times: Donors Pledge $41 Million to Monitor Thawing Arctic Permafrost

Arctic Today: A new program aims to monitor, mitigate and adapt to Arctic-wide thaw

Alaska Public Media | Talk of Alaska: Collaborative project Permafrost Pathways tackles a thawing Arctic

Alaska Public Media | Alaska Insight: Tracking permafrost thaw will help Alaska communities better adapt to climate change

Time Magazine: Quick Talk with Dr. Sue Natali

The Carbon Copy: We need to talk about permafrost and its impact on the climate

The Economist: The Alaskan wilderness reveals the past and the future

The Economist: What does the world’s thirst for oil mean for Alaska’s ice?

KYUK Radio: Tracking global warming in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta

Reuters: Why Arctic fires are releasing more carbon than ever

Stay connected to Permafrost Pathways—sign up for email updates and follow us on Instagram and Twitter. Need to catch up? You can also explore our stories page for the latest project news.

Go to top