Alaska Native communities face winter preparation challenges in the wake of Typhoon Merbok

Family camps and subsistence cabins after the storm in Nome, Alaska. Photo by Zachariah Hughes / Anchorage Daily News

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

September storm highlights urgent need for climate adaptation frameworks in Alaska

In mid-September, Typhoon Merbok sent a 10-foot storm surge and 50-foot waves crashing over homes, schools, roads, and vital infrastructure in western Alaska, causing extreme flooding across 1,000 miles of coastline. Now, rebuilding efforts are in a race against time as affected communities attempt to recover from the storm that ravaged nearly 100 small and rural Native villages in the middle of preparations for winter.

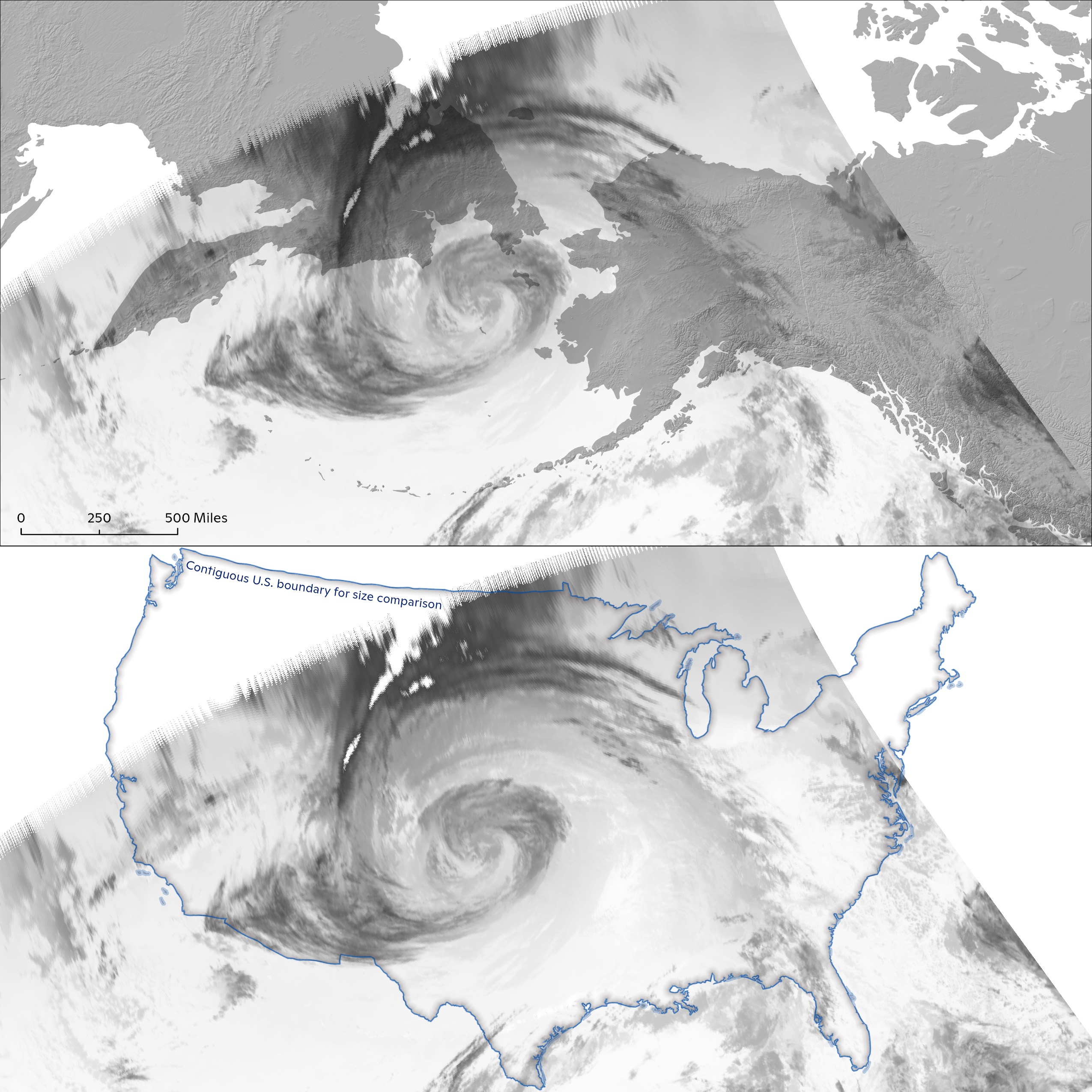

Animation and map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

An outsized storm with outsized impacts

Typhoon Merbok formed over the northwestern Pacific Ocean on September 9 and spun up into the Bering Strait over the week that followed. The National Weather Service highlighted the importance of recognizing the size of the storm, reporting that it was so large that the impacts spanned almost the entire Alaskan shoreline, while the sun took three hours to fully set on it. According to Woodwell Deputy Director, Dr. Jennifer Francis, a storm like this forming so far north is unusual. Its destructive power was made possible by warmer-than-average ocean temperatures.

“It could achieve this feat, rather than weakening as most storms do, because it traveled over marine heatwaves—areas where ocean temperatures are much higher than normal,” says Dr. Francis. “Tropical storms are fueled by the abundant moisture evaporating from these hotspots. This extra boost of energy allowed Merbok to form and strengthen in an area of the Pacific Ocean where tropical storms are uncommon.”

The abnormal nature of the storm contributed to its widespread devastation, especially in the western part of the state where remote Alaska Native villages were particularly affected, due in part to the unique vulnerability of their locations on low lying landscape. Cingik/Siŋik (Golovin), Cev’aq (Chevak), Naparyaarmiut (Hooper Bay), Niugtaq (Newtok), and Sitŋasuaq (Nome) were among the most heavily impacted communities. Homes floated away, sea walls were damaged, roads and airstrips swallowed, and many subsistence camps—harvest preparation cabins significant to Alaska Native food sovereignty and cultural perpetuity—were destroyed.

Inundation after Typhoon Merbok in the Inupiat village of Golovin, Alaska. Photo by Ian Gray / U.S. Coast Guard

The infrastructure in rural Alaska, which has already been debilitated by decades of thawing permafrost, was not designed to withstand a storm of Merbok’s magnitude. Several communities lost electricity, telecommunications, and internet connectivity—all significant means of accessing vital and potentially life-saving disaster aid. In a September media briefing, U.S. Rep. Mary Peltola of Alaska said, “I’m not sure that we have been building things for storm surges that see 90-mile-an-hour winds.”

Nome Council Highway on September 21, 2022. Photos by Shea Oliver / Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities

Environmental data and monitoring, where rural Alaska gets left behind

Unlike with cyclones that strike the lower 48 states, like recent Category 4 Hurricane Ian, there is comparatively little data and monitoring for storms in Alaska. In a post on Twitter, climate scientist Dr. Rick Thoman at the University of Alaska Fairbanks said, “one of the many difficulties with coastal flood forecasting in western Alaska is the lack of real-time observations.”

Lack of technical assistance and environmental monitoring support in rural Alaska present major barriers for communities looking for data that can help them prepare for and recover from rapidly approaching weather events, like storms and wildfires, as well as adapt to ongoing environmental disasters, like permafrost thaw and coastal erosion, caused by long term climate change. The absence of this data means government agencies like the National Weather Service do not provide forecasts at the right level of detail to communities in the region—many of which aren’t even part of the existing forecast system at all. Currently, climate experts like Dr. Thoman give the Alaska Institute for Justice weekly storm forecasts that the organization then distributes directly to the Tribes they’re working with.

Storm surge flooding caused by Typhoon Merbok in western Alaska. Photo by Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities.

“The typhoon has shown the extent of these extreme gaps in the disaster preparedness necessary to meet community needs ahead of storm events. The aftermath also emphasized the extreme environmental vulnerability because these communities are without road access and cannot easily evacuate,” said Permafrost Pathways partner Dr. Robin Bronen from the Alaska Institute for Justice, a human rights attorney who has been working with Alaska Native Tribes on climate adaptation and relocation since 2007. “There’s no higher ground to go to, which means storm forecasts are critically important so communities can stay informed, figure out what their evacuation plans are, and make sure people get to safety before the storm hits.”

The Alaska Ocean Observing System (AOOS), a NOAA-affiliated effort to improve access to ocean data, notes on their website that, “unfortunately, Alaska coasts have historically received less attention than the rest of the continental U.S. in terms of real-world observations, and as a result suffer from a higher degree of uncertainty in terms of understanding coastal water level, current and wind-wave simulation capacity. At present, there are only four year-round verified NOAA National Water Level Network (NWLON) water level stations along the thousands of miles of coastline in western Alaska and the Alaska Arctic.”

A devastated subsistence fish camp in Nome, Alaska. Photo by Jeremy Edwards / FEMA

More subsistence camp devastation in Nome, Alaska. Photo by Zachariah Hughes / Anchorage Daily News

Timing ahead of winter threatens rural community subsistence

The timing of Typhoon Merbok was particularly devastating for Alaska Native communities who heavily rely on subsistence livelihoods. Autumn is an important time for harvesting and preparing critical subsistence food sources like berries, fish, moose, and other game that can be stored throughout winter. Reports from local community members on the ground indicate many hunting and fishing cabins, drying racks, and smokehouses have been damaged or swept away entirely. Subsistence cabins are not only essential to traditional harvesting practices and the Yup’ik, Inupiaq, and other Alaska Native cultures in the region, but they also serve as educational childcare in the summer, support local economies, and offer multigenerational connection and community between relatives and longtime friends.

In addition to subsistence camps, many residents lost boats, snow machines, and other vehicles necessary to participate in traditional harvests, as well as a substantial amount of food gathered during the summer and early autumn that was already stockpiled for the colder months ahead—leaving many concerned about how they will sustain their communities as winter descends.

Deanne Criswell from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Representative Mary Peltola, and Senator Lisa Murkwoski surveying damage in Nome, Alaska. Photo by Jeremy Edwards / FEMA

As the storm’s impact spread throughout the weekend, Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy issued a state disaster declaration for western Alaska on September 17. Three days later, he submitted a request for a federal disaster declaration—which was approved by President Biden on September 23 as emergency response groups began coordinating relief, but residents questioned the late timing of these decisions given the environmental vulnerability of the region and the advanced warning of the storm’s severity. While it’s important to recognize that the Biden administration is stepping into the climate adaptation space in ways no administration has ever attempted before, Dr. Bronen said responding to environmental hazards after communities have already suffered substantial loss is not enough.

“What is the long-term solution that Tribes need to be focused on to make sure that when an extreme weather event happens again, they are less environmentally vulnerable than they were during this storm that just happened? What’s the long-term adaptation strategy that they need funding for? Then the federal government needs to figure out the mechanisms to get that funding to Tribes. These are the conversations that need to be happening now,” Dr. Bronen said.

Unique landscape in the Alaska Native village of Atmautluak. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Many Alaska Native villages are in the most remote parts of the large state and aren’t accessible by road—only by plane or barge. When an environmental disaster like Merbok makes landfall, lack of state-supported preparedness can leave communities cut off from food, supplies, equipment, and disaster aid when storm surges erode coastlines and submerge airstrips.

“The storm was so severe that even hundreds of miles into interior Alaska, communities were feeling the impacts. Tribes all along the Yukon were experiencing high winds and waves on the Yukon River nearly six feet tall, which is an unusual event,” said Brooke Woods, a community member from the Alaska Native village of Rampart and the Arctic policy coordinator at Woodwell Climate Research Center. “After the storm hit, traveling in Rampart became dangerous and residents were advised not to leave the village, which was concerning because many families were in the midst of finishing up their moose hunting season.”

Storm surge damage in Alaska caused by Typhoon Merbok. Photo by Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities

Persistent climate hazards loom

The Arctic is warming three to four times as fast as other parts of the globe. Warmer temperatures will make storms like Merbok much more likely in the future and further exacerbate other ongoing climate hazards such as permafrost thaw, flooding, and erosion. At least 73 Alaska Native villages are already grappling with difficult decisions about community-wide relocation. $5.5 billion worth of Alaskan infrastructure is expected to be damaged as a result of climate change this century, yet climate adaptation governance frameworks still do not exist to address this mounting human rights crisis.

“Another two to three storms with this magnitude, everything will be washed out there,” Charlie Brown, mayor of the Inupiat village of Golovin, told the Alaska Beacon.

Typhoon Merbok has laid bare the urgent need for climate adaptation strategies, hazard mitigation policies, and emergency preparedness in the Alaskan Arctic and subarctic. To begin the process of developing these systems, Permafrost Pathways has partnered with Alaska Native villages to co-create Indigenous-led adaptation and relocation plans. Alongside project partners at the Alaska Institute for Justice, Permafrost Pathways is also advocating for more federal support for solutions that are developed with and led by Alaska Native villages already spearheading efforts to protect and prepare their communities against the impacts of climate change.

“This storm was a perilous reminder that we are failing to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions,” Dr. Bronen said. “At the consequence of millions of people not only in Alaska and the rest of the United States, but also people around the world who live in coastal communities where the land on which they are currently living is going to be permanently submerged.”

This story includes contributions by Sarah Ruiz.

Go to top