How do we create equitable solutions to permafrost thaw? Together.

Tiffany Windholz, Reggie Tuluk, Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison for the Native Village of Cev’aq, and Darcy Peter downloading data from a temperature sensor. Photo by Aurora Taylor / Permafrost Pathways

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost Pathways connects science, people, and policy to advance Arctic justice

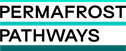

A Permafrost Pathways study informed one of the biggest headlines in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) 2024 Arctic Report Card, sending a clear but alarming message to the world: more than one-third of Arctic-boreal region has shifted to a source of carbon. The sobering results, mentioned in over 700 news stories from 42 countries, shed light on the urgency of Arctic research.

Over the past three years, Permafrost Pathways has been advancing Arctic research through an inclusive and interdisciplinary approach—one that intertwines rigorous Western science with Indigenous Knowledge to co-produce critical insights into Arctic warming and generate equitable solutions to the rapidly growing issue of permafrost thaw.

Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Kelcy Kent and Dani Trangmoe working on a carbon flux tower installation in Council, Alaska.

Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

When we invest in Arctic research, the once impossible becomes possible

The Arctic tundra was once a crucial carbon sink, but has now become a net emitter of carbon dioxide and a consistent source of methane. This shift, identified in a study led by Woodwell Climate Research Scientist Dr. Anna Virkkala, is likely due to rising emissions from thawing ground and increased wildfire activity.

“While we found many northern ecosystems are still acting as carbon dioxide sinks, source regions and fires are now canceling out much of that uptake and reversing long-standing trends,” said Dr. Anna Virkkala in a January press release about the newly published research.

Average terrestrial CO2 balance during 2001-2020 based on a synthesis of field measurements and machine learning models.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

This finding was supported by Permafrost Pathways’ expansion of the Arctic-boreal carbon monitoring network and the compilation of thousands of data points from active and historical monitoring sites. In 2024, four new carbon flux towers were installed across key Arctic ecosystems, including Nunavut, Canada, and Alaska, and researchers provided technical assistance to existing towers in Canada and Russia. The scarcity of data on carbon emissions and uptake from permafrost lands is a major barrier to fully accounting for permafrost thaw in global carbon budgets.

Permafrost Pathways installed carbon flux towers in Qausuittuq (Resolute Bay) and Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), Nunavut in 2024.

Photos by Dani Trangmoe and Patrick Murphy / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“Having data in these under-sampled areas will greatly help our understanding of Arctic-boreal carbon cycling. Models depend on their data to represent the full spread of conditions across the model, which is lacking,” says Dr. Kyle Arndt, who leads the Arctic Carbon Monitoring Network team for Permafrost Pathways. “ This project is unique in that it enabled us to measure less-studied areas with the goal of filling data gaps and really capturing the big picture. So, to install these towers in crucial ecosystems in a relatively short time and collect that necessary data year-round is pretty remarkable.”

These efforts, supported by an international network of collaborators, have contributed to the development of the most comprehensive database of carbon dioxide and methane fluxes ever assembled across the permafrost region. The Arctic-boreal carbon flux database contains roughly 23,000 monthly observations compiled from both active monitoring sites and historical data.

Additionally, the Permafrost Pathways team is using novel methods to map disturbances—such as wildfire and sudden ground collapse—at high spatial resolution by leveraging commercial satellite imagery and artificial intelligence. These events have the potential to double the warming effect of permafrost thaw, but they have not been accounted for in international assessments used to guide climate policy.

“We’re working with partners at Esri, the global leaders in mapping software, to create the first-ever circumpolar map of abrupt thaw events, a dramatic and important type of disturbance that can generate high levels of carbon emissions. The tools and data we develop will not only allow us to better monitor major disturbances, but also provide crucial information needed to project these into the future,” said Woodwell Climate Associate Scientist Dr. Brendan Rogers, who co-leads the project.

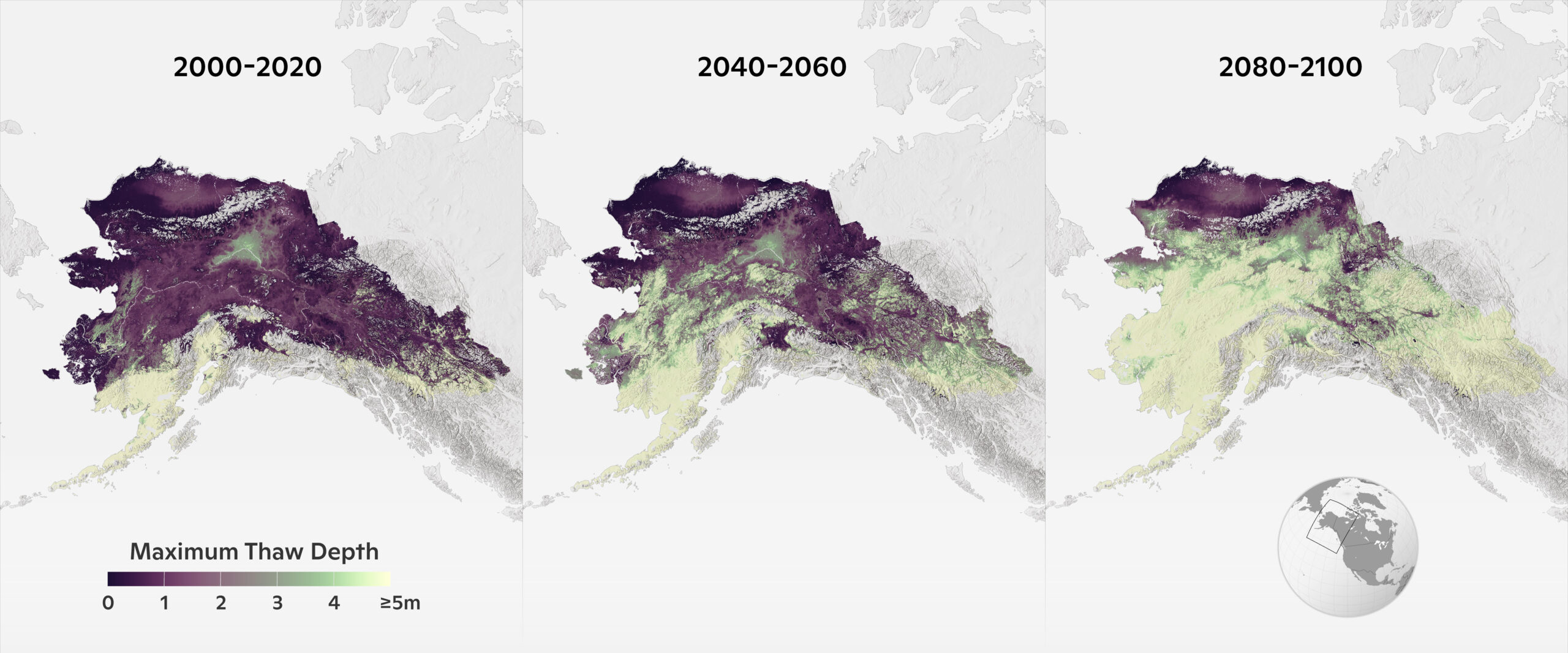

Past and projected maximum thaw depth in Alaska.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost Pathways and collaborators are also working on improving Arctic ecosystem models to better predict future changes in permafrost and Arctic emissions. Preliminary findings show significant thawing of permafrost across Alaska and western Canada, and future research will expand the model’s scope to the entire Arctic.

Aurora Taylor (formerly AIJ) and Cynthia Paniyak look at maps in Chevak.

Photo by Tiffany Windholz / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic science must include Indigenous Knowledge

While Western scientists continue to refine their understanding of the climate impacts of permafrost thaw, communities on the ground have been actively witnessing and experiencing those impacts for decades.

“You really gotta go out and watch this stuff. It’s really changing, things are really wrong,” Elder Wilson Justin, Athabascan Dine, recalls his uncle telling him about the cascading effects of permafrost thaw in the late 1970s. “So I went out to look at the permafrost and was flabbergasted that it had disappeared.”

Understanding the larger picture of Arctic warming is not possible without the knowledge and expertise of Arctic Indigenous communities who have called the region home since time immemorial.

Permafrost Pathways has prioritized the integration of Indigenous and Western knowledge systems to support climate adaptation in Alaska and beyond. Working closely with Alaska Native community partners, the project is co-creating Indigenous-led strategies to address the impacts of permafrost thaw, flooding, and erosion.

Tribal Liaison Maamcuk Foss from the Native Village of Akiak and Woodwell Climate’s Tiffany Windholz mapping erosion.

Photo by Darcy Peter / Woodwell Climate Research Center

One of the standout developments has been the co-creation of a flood model that factors in sinking ground from thawing permafrost. The model was developed using information from sensors installed in communities and on-the-ground knowledge from Tribal collaborators, ensuring that results are deeply rooted in local observations and Indigenous expertise.

In addition, Permafrost Pathways prioritizes skills training to build community capacity and inform adaptation decision-making. At a spring mapping workshop, Tribal liaisons and representatives gained introductory Geographic Information System (GIS) skills, learning how to map Indigenous place names and develop digital storytelling tools.

At the Alaska Forum on the Environment conference, Tribal Liaison Brian Carl from the Native Village of Qipneq (Kipnuk) presented a map he created that illustrates the extent of community flooding.

Photo by Tiffany Windholz / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“We really prioritize relationship-building and working in partnership. A large part of that is skill-sharing because projects come and go, so we recognize the importance of community capacity-building in our adaptation work,” said Research Assistant Tiffany Windholz, a member of the Permafrost Pathways adaptation team who works closely with Alaska Native community partners on environmental monitoring and GIS capacity-building.

Permafrost Pathways provides ongoing one-on-one GIS training with Alaska Native community partners, who are now leading efforts to map climate impacts in their communities. Several partners are applying these GIS skills to map shoreline erosion, flooding, and proposed relocation sites for threatened infrastructure.

Tribal Liaison Maamcuk Foss from the Native Village of Akiaq (Akiak) is working on mapping Indigenous place names in Akiaq to help younger generations connect with their traditional language. “I’m learning [mapping and GIS] stuff every day,” said Foss. However, the learning in this work is mutual. Foss is also working with Research Assistant Jackie Dean to map Akiak’s rapidly eroding river shoreline, providing local knowledge and expertise critical to developing accurate representations of climate impacts that Akiaq is up against.

The Permafrost Pathways team meeting with Rep. Peltola’s office in Washington D.C.

Photo by Tierney Cross

Centering Arctic voices in conversations with policymakers

Permafrost Pathways’ work with communities has begun to establish adaptation strategies that could be scaled up to serve as a national framework. As climate change accelerates, getting the best available science on the desks of policymakers and centering the voices of those on the frontlines is a top priority.

Influencing policy in Alaska has historically been difficult due to challenges in federal interagency coordination on climate adaptation and hazard responses. In the village of Cev’aq (Chevak), the severe erosion of a culvert is threatening a steam house and inching closer to a village home. Despite multiple agencies being aware of the ongoing crisis, coordinated action has been slow because of jurisdictional limitations, leaving Cev’aq in a dangerous state of uncertainty.

Reggie Tuluk and Jackie Dean measuring the erosion of a culvert in Ceva’q.

Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Here, Permafrost Pathways was able to provide support, working with Tribal Liaison Reggie Tuluk to conduct environmental surveys and map the rate of erosion. Together, the project and Cev’aq were able to leverage these outputs to draw attention from necessary state and federal entities.

“Putting this expertise on a map makes people pay more attention to the environmental hazards that the community is leading efforts to address,” said Dean, who is working with Tuluk to co-produce erosion maps.

Permafrost Pathways has also been cultivating relationships with Congressional leaders, including staff from the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, the House Sustainable Energy and Environment Coalition, and Senator Lisa Murkowski. In September 2024, the team met with Senator Murkowski to advocate for legislative solutions to climate risk mitigation and funding for permafrost research.

Morris Alexie and Woodwell Climate’s Laura Uttley during a congressional meeting with Sen. Lisa Murkowski in Washington D.C.

Photos by Tierney Cross

“I’ve met twice with Murkowski’s office over the past couple of years,” said Morris Alexie, Tribal Liaison for the Native Village of Nunapicuaq (Nunapitchuk). “She was hearing our cry of not understanding the complete FEMA processes for disaster declarations, especially when it comes to the required paperwork and language translations. So far, I see that she has been working towards alleviating those barriers for Tribes in Alaska.”

Morris Alexie, Dr. Sue Natali, and Jackie Dean in Nunapicuaq, Alaska.

Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Moving forward together in a time of uncertainty

Drastic shifts in both the U.S. and international political landscapes have thrown up obstacles for Arctic research. Continued complications from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and recent actions by the new U.S. federal administration that target science funding, research infrastructure, and climate adaptation programs will necessitate more creative and thoughtful approaches to the project’s objectives going forward.

“We have experienced slow progress on expanding carbon monitoring in Russia, and we anticipate challenges to advancing climate policy in the United States,” said Dr. Sue Natali, Project Lead and Senior Scientist at Woodwell Climate.

But the team continues to move forward, investing in the strength of the network they have helped build between policymakers, Arctic communities, and scientists.

“Despite the uncertainty ahead, we’ve been highly adaptable in identifying and pursuing new paths to advancing equitable solutions to permafrost thaw,” says Natali. “We remain committed to our scientific collaborators and Indigenous partners in continuing to work toward Arctic justice and resilience with our communities of practice, without which progress in this work would not be possible.”

Go to top