Establishing an Arctic carbon monitoring network to better address the climate crisis

Eddy covariance tower site in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Alaska. Photo by Mitch Korolev / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Program Director and Senior Scientist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost Pathways is increasing the coverage of Arctic carbon monitoring sites to fill data gaps and reduce uncertainty in emissions estimates

A major goal of Permafrost Pathways is to ensure that permafrost carbon emissions are accounted for in global climate policy. But first, we need to be able to assess the current carbon balance of the Arctic.

Here’s what we need to know: Is the Arctic a net carbon sink, as it has been for tens of thousands of years, meaning that plants are absorbing more carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere than is being released from soils as both CO2 and methane (CH4)? Or has the scale tipped—is the Arctic now a carbon source, meaning that soils and permafrost are releasing more CO2 and CH4 than plants can sequester?

Restored eddy covariance tower at the Scotty Creek Research Station in Canada. Photo by Marco Montemayor / Woodwell Climate Research Center

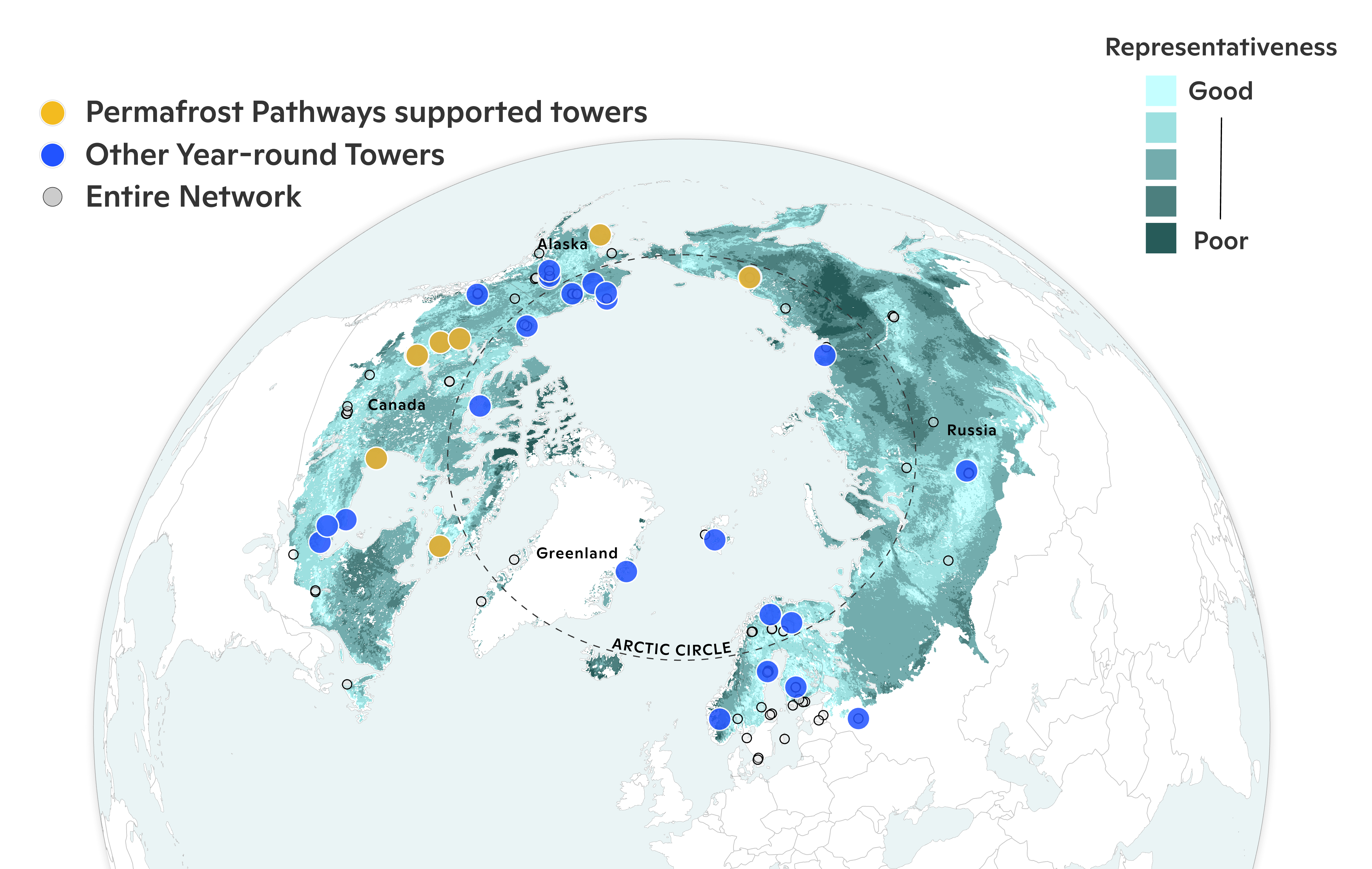

To track CO2 and CH4, we use the eddy covariance method, which directly measures greenhouse gasses as they move between soils, plants, and the atmosphere. Currently, there are about 64 active eddy covariance towers across 5.5 million square miles of the entire Arctic region that measure both CO2 and CH4 fluxes. Only 39 of those towers run throughout the year. These criteria are critical because soil microbes can produce CO2 and CH4 year-round—even during the long, frozen winters—and because CO2 and CH4 are two of the most potent greenhouse gasses. Running this instrumentation throughout the winter is particularly challenging in the Arctic, as many locations are off the power grid and there is no solar power during the dark winters of the high north.

Arctic carbon monitoring network. Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Over the next several years, we will be installing 10 new, strategically placed eddy covariance towers and supporting existing towers by providing equipment for year-round measurements of both CO2 and CH4. While 10 may not seem like a big number, the keywords here are strategically placed. Using satellite data, maps of important environmental and ecological variables, and statistical analyses of how representative the current eddy covariance network is, we have identified priority locations for new installations. The Siberian Arctic and the Canadian High Arctic are particularly underrepresented, so our team is partnering with local and Indigenous communities on the ground to coproduce knowledge about environmental changes they are experiencing and support community-led monitoring.

Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Kyle Arndt working on the eddy covariance tower installation in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada in summer 2022. Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

In 2022, we installed a new eddy covariance tower in Churchill, Canada and supported six existing towers across Canada and Alaska. We are now working with local Arctic researchers and Arctic Indigenous communities to develop a plan to establish additional towers in Canada and Siberia. Our recent fieldwork included a trip to southwest Alaska earlier this year to troubleshoot equipment issues at a remote site accessed by ski plane. In March 2023, our team traveled to Northwest Territories, Canada to fix equipment at the Scotty Creek tower site that burned down during an unprecedented late-season wildfire in October 2022. Last month, our team visited Nunavut, Canada to meet community members and discuss Indigenous-led environmental monitoring and the potential for future tower installations.

By combining these new data with improved models, we will soon have a better understanding of the current and projected carbon balance of the Arctic, and what that means for our shared climate future.

Go to top