Alaska Native communities host partners from Permafrost Pathways

Woodwell Climate’s Sol Cooperdock and Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison for the Alaska Native village of Nunapicuaq Morris Alexie checking on a community weather station. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

This summer, Woodwell Climate Research Center and the Alaska Institute for Justice visited six community partners in remote Alaska

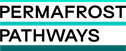

In August, researchers from the Permafrost Pathways team visited several Alaska Native communities including returning visits with longtime partners in Kuigilnguq and Nunapicuaq, as well as first-time visits with new partners in Akiak, Chevak, Chinik (Golovin), and Kipnuk. The team met with community members and Tribal liaisons to discuss community needs, investigate and map landscape change, install environmental monitoring equipment, and conduct relocation site assessments to inform and advance community-led climate adaptation planning and decision-making.

Left: Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison Maamcuk Foss and Dr. Sue Natali discussing flood water levels and building elevation in Akiak.

Right: Chinik (Golovin) from above.

Photos by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Several Permafrost Pathways partner communities that project researchers visited this summer are experiencing compounding environmental hazards caused by permafrost, flooding, and erosion. Threats include public health concerns due to leaching landfills and sewage lagoons; thaw-induced structural damage to roads and boardwalks; inaccessibility of piped water due to unstable lands; inability of barges to deliver fuel due to sedimentation of rivers; degradation of land, infrastructure, and subsistence resources.

Woodwell Climate’s Greg Fiske drilling into the tundra in Golovin. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

The Alaska Native villages of Nunapicuaq and Kuigilnguq, who have been part of Permafrost Pathways since 2022, but have been working with AIJ’s Dr. Robin Bronen and Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Sue Natali for much longer, decided to relocate their communities. Researchers from Woodwell Climate returned to Nunapicuaq and Kuigilnguq to support relocation site assessments—including measuring ground ice content, permafrost temperature, and structure; as well as water quality testing—to help move the process forward.

Left: Dr. Alexander (Sasha) Kholodov, a researcher from the University Alaska Fairbanks, sampling ground conditions in Nunapicuaq.

Right: Morris Alexie, Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison for Nunapicuaq and Dr. Kholodov during a site assessment.

Photos by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost sampling in Nunapicuaq’s potential relocation site showed promising results with low ground ice and coarse, compacted substrates near the surface—good for supporting infrastructure—confirming community knowledge of conditions at the new location. This information will be used by Nunapicuaq and government agencies to determine if these sites are viable relocation options based on current and future environmental conditions, and will also guide the project’s efforts to develop federal relocation site assessment guidelines, which currently don’t exist.

Left: Permafrost Pathways tribal liaison from Kipnuk, Chris Dock, collecting water samples.

Right: Reggie Tuluk, Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison for Chevak, drilling for soil samples.

Photos by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

First-time visits with new community partners in Akiak, Chevak, Golovin, and Kipnuk involved introductions and assessing the most urgent community needs. Community-led environmental monitoring included water sampling to test for mercury, other trace metals, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS); and tracking erosion—a climate hazard that on-the-ground measurements are especially critical to have due to the lack of satellite data. In addition to developing and implementing responses to adaptation needs, the project’s adaptation work also involves establishing a framework for integrating this knowledge into an adaptation toolkit that will be broadly applicable for Arctic communities in Alaska and beyond.

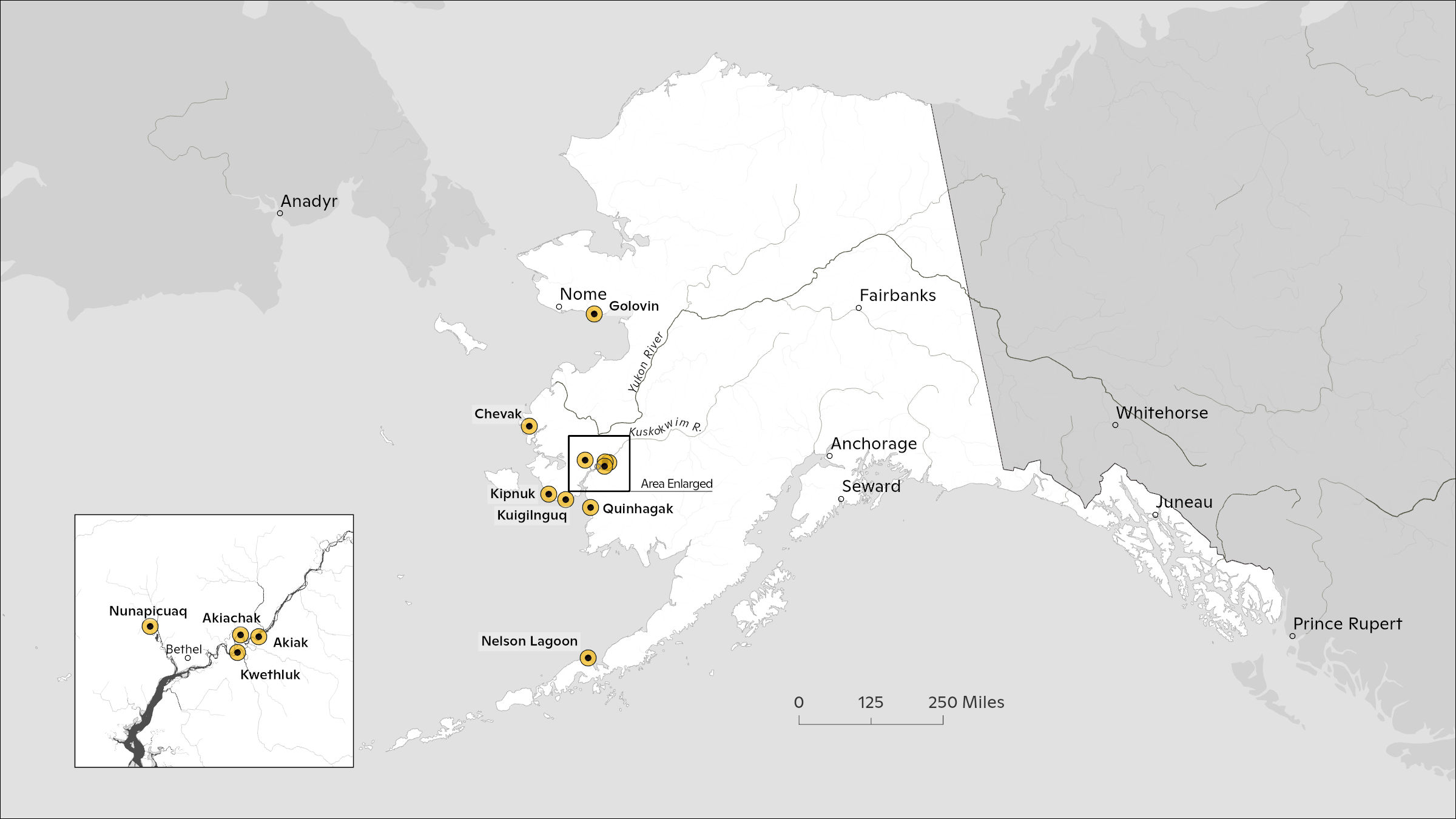

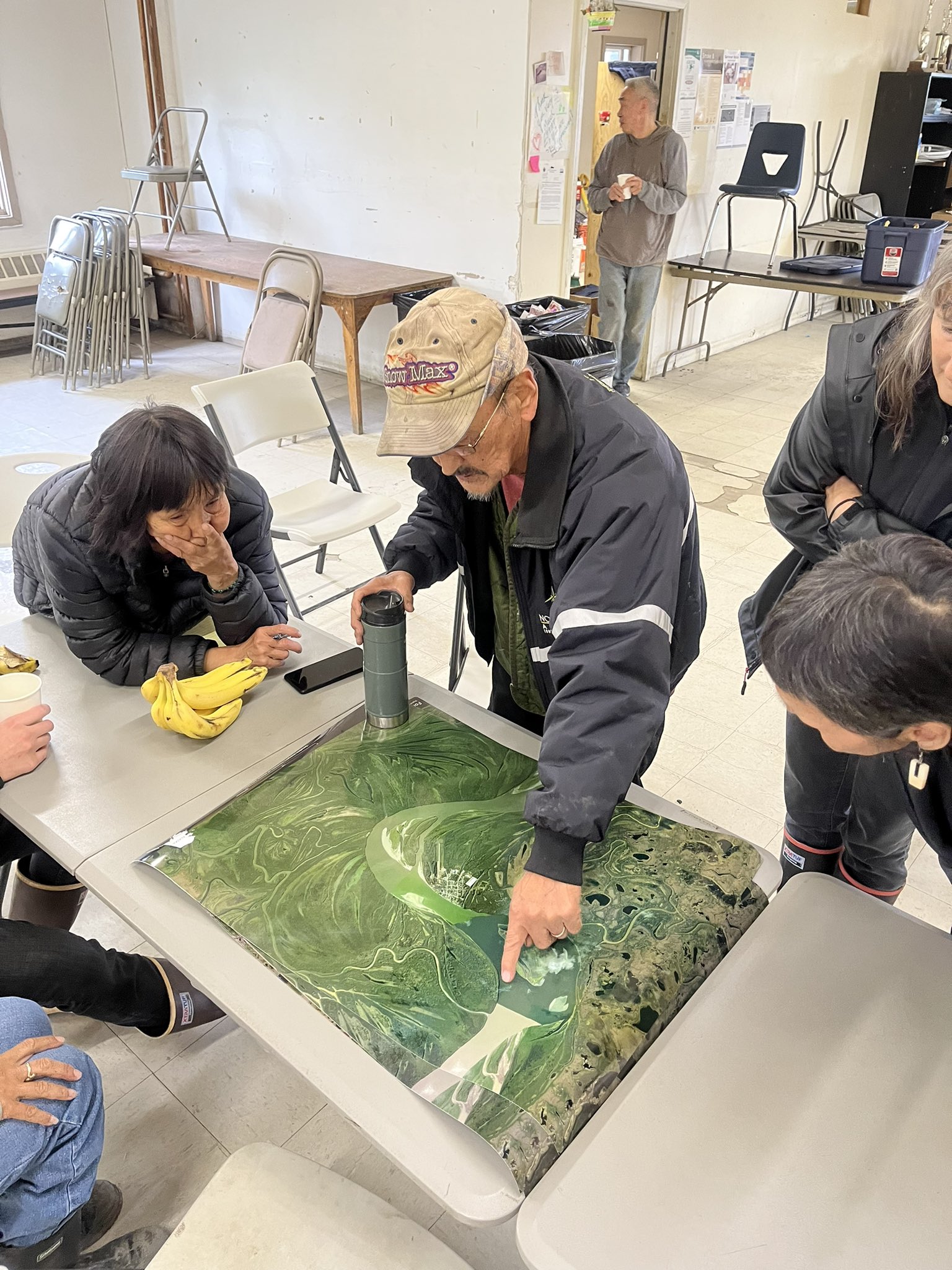

Left: Maps bringing people together in Golovin.

Right: Satellite imagery breaks the ice in Akiak.

Photos by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Several maps were also in tow this summer thanks to Greg Fiske, Woodwell Climate’s Senior Geospatial Analyst, who works closely with community members to map landscape change and co-produce information that combines Indigenous Knowledge with Western science and geospatial technology for more accurate representations of how the environment has been changing in their villages.

Left: Gary Evon from Kuigilnguq working with Greg Fiske to map community flooding. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Right: Kuigilnguq satellite imagery. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“Alaska Native people have a deep connection to and understanding of the land,” Fiske said. “Putting a map in front of our Indigenous partners always inspires the telling of unique stories and the sharing of environmental expertise and historical observations from communities that have long been experiencing climate change in their homelands.”

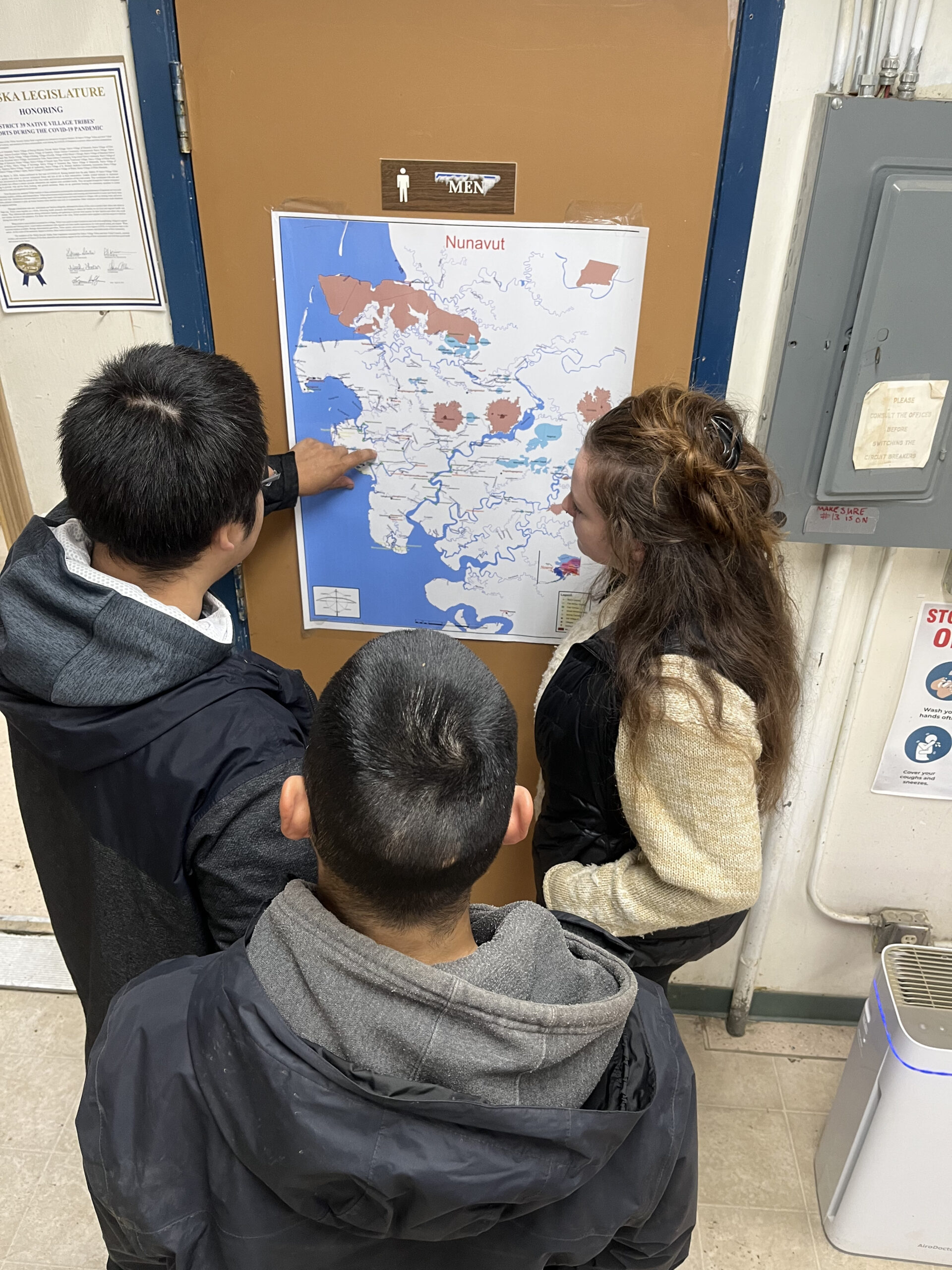

Left: Reggie Tuluk pointing to Alaska Native place names in Chevak.

Right: Mapping our places: Voices from the Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative—a book about Indigenous mapping projects. Photos by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

The co-production of knowledge is a major pillar of the Permafrost Pathways project and has been especially influential when co-producing maps with community observations on the ground. In Kipnuk and Chevak, the Indigenous mapping movement is alive and well. These communities are putting place names in Yup’ik and Chupik back on the map to decolonize place and space while preserving traditional knowledge, Alaska Native languages, and cultural history. Chevak and Kipnuk will then work with Fiske and Tiffany Windholz, a Research Assistant in the Arctic program at Woodwell Climate, to make this information spatial and accessible in the future.

“What does it mean to prioritize the co-production of knowledge in our work? Decolonization is a big part of this. Understanding the cultural history of the Tribes that we’re working with, why communities are where they are, how decisions are being made by academics and the federal government, how we develop methods together, how we define the problem. There’s a lot that is taken into consideration. Trust, equity, and respect are always at the core of everything we do,” said Dr. Sue Natali. “Co-production makes the science and the outcomes better.”

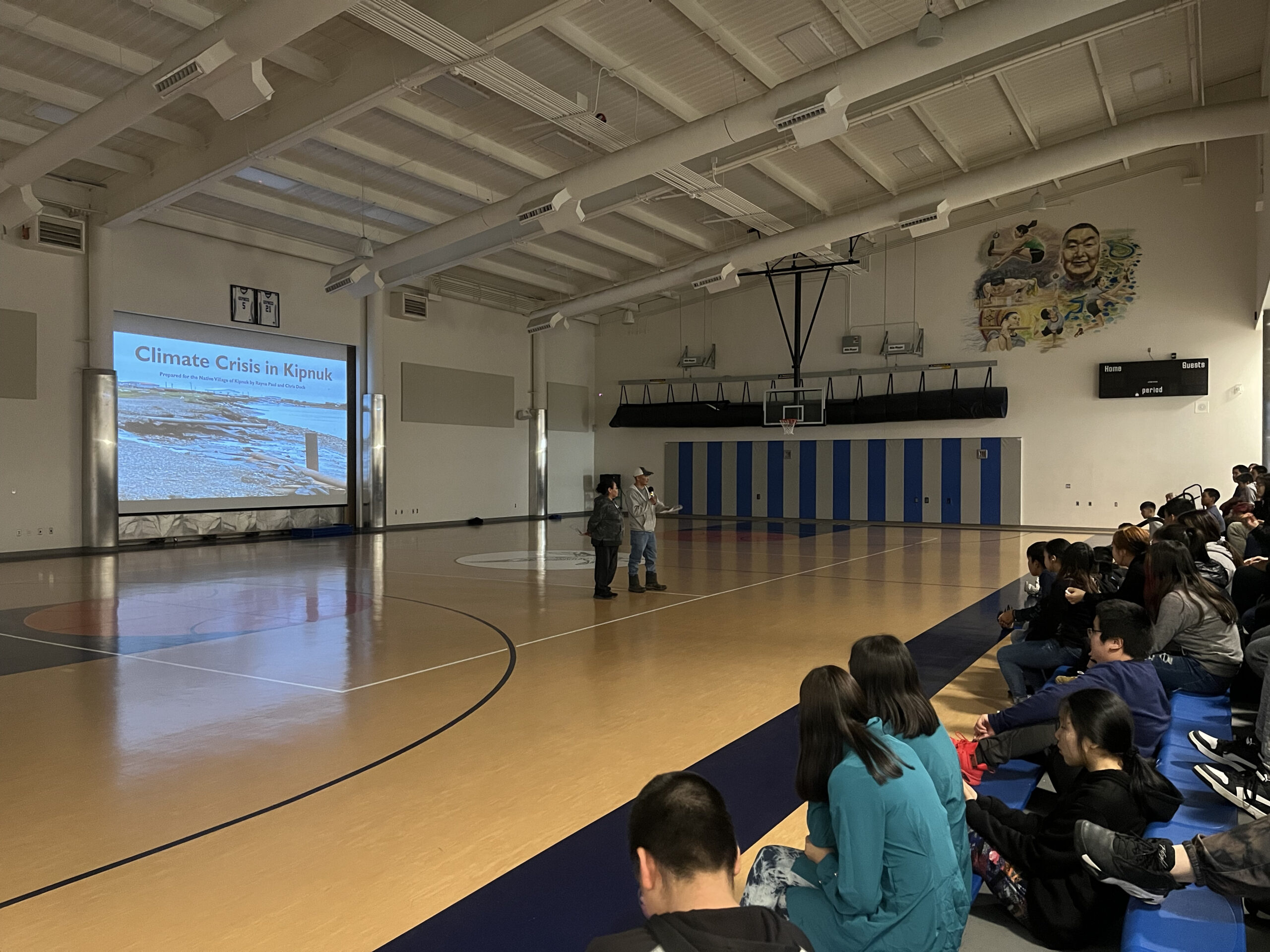

Top: Community leaders in Kipnuk giving a presentation to local youth about the impacts of climate change in their village. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Bottom: Morris Alexie and AIJ’s Ben Baldwin navigating the coast in Nunapicuaq. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

The summer in rural Alaska was spent relationship building, sharing meals, storytelling, having many laughs, and advancing the climate adaptation planning that communities are leading to protect themselves and their lifeways from the impacts of climate change. The project’s onsite environmental assessments and collaborations with Alaska Native community partners are not only providing direction for immediate technical assistance and adaptation planning, but also spearheading longer-term policy change.

“Alaska Native communities are helping federal agencies design relocation governance frameworks as they respond to Arctic warming,” Dr. Natali said. “Our Tribal partners leading these strategies in Alaska are ultimately influencing future climate legislation and adaptation policies that will benefit people across the country and the world.”

Go to top