Adaptation workshop brought together Alaska Native communities and federal agencies

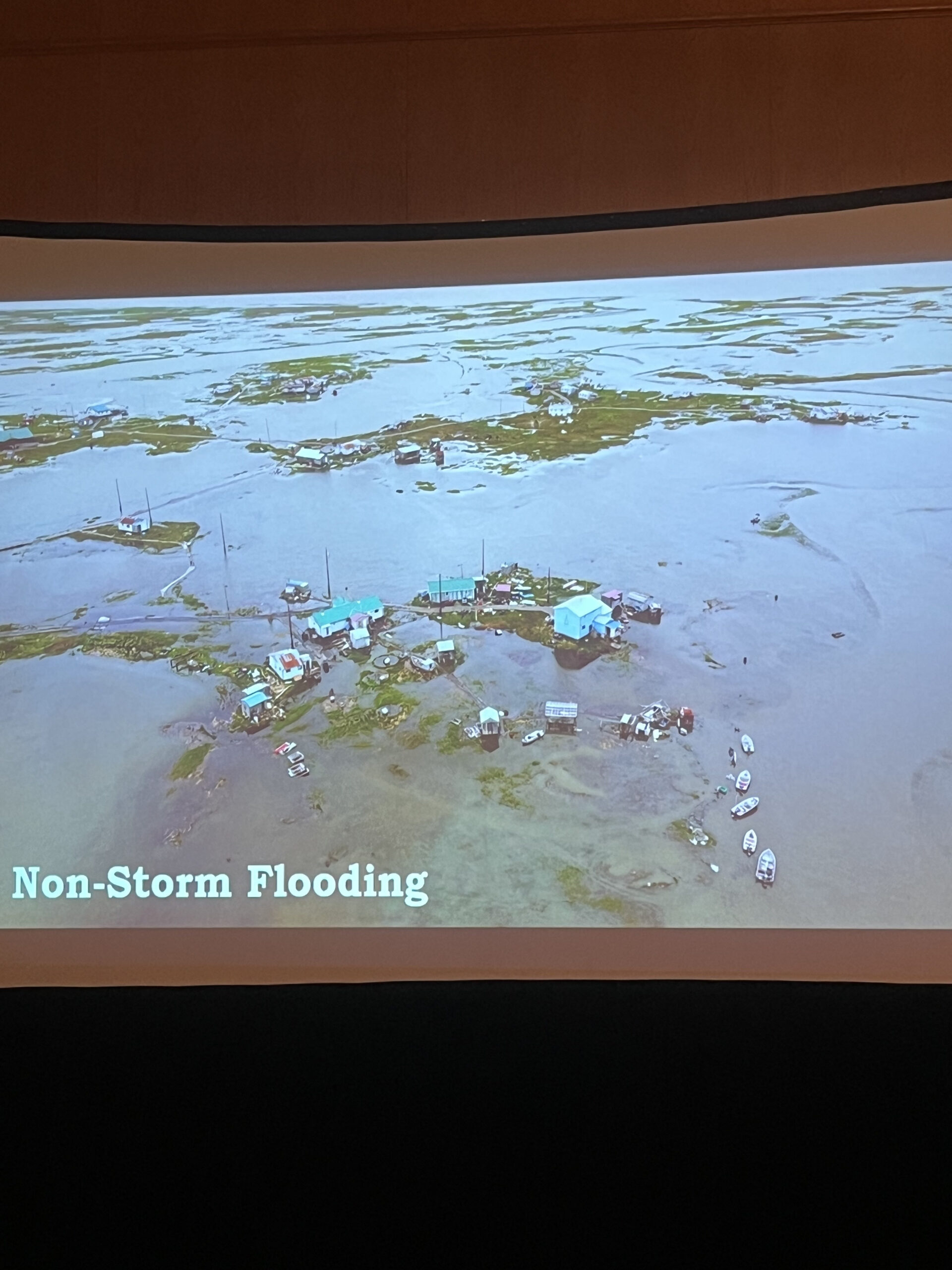

Elders from Kwethluk showing the Permafrost Pathways research team where the Kuskokuak River is eroding — threatening to inundate their community. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

The September workshop facilitated Tribal-led conversations with government agencies focused on climate impacts in Alaska

Last month, the Alaska Institute for Justice (AIJ) hosted a “Rights, Resilience, and Community-Led Adaptation” workshop on Dena’ina homelands in Anchorage, Alaska alongside partners from Woodwell Climate Research Center, the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School, and the Alaska Native Science Commission. AIJ has been organizing these workshops since 2016 to create a space where Tribes can share their expertise with each other and connect face-to-face with federal and state government representatives to access resources and technical assistance. This year, the workshop was part of the Permafrost Pathways project’s ongoing efforts to support Indigenous-led adaptation strategies and relocation governance frameworks for communities responding to rapid Arctic warming.

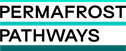

Permafrost Pathways Alaska Native community partners. Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Over 65 Alaska Native community members and more than 60 representatives from state and federal agencies—including the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), the Department of the Interior (DOI), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Denali Commission, Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities—convened for two full days of community presentations, panel discussions, and round tables to give Tribes the opportunity to share their experience of climate hazards that are threatening the health and well-being of their communities, and to discuss opportunities for federal aid and support.

A building placed on risers to mitigate sinking into the thawing permafrost below in Kuiqilnguq. Photo by Gary Evon / Former Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison

“2023 has shown all too clearly that climate change is here, with intensifying and unique impacts on the environment,” Permafrost Pathways Co-Lead and Executive Director for the Alaska Institute for Justice, Dr. Robin Bronen said in a statement. “Our support at Alaska Institute for Justice to ten rural Alaska Native Tribes is positioned to deliver on climate adaptation objectives together, while protecting the human rights of Alaskans and building a more sustainable, safe, and resilient future.”

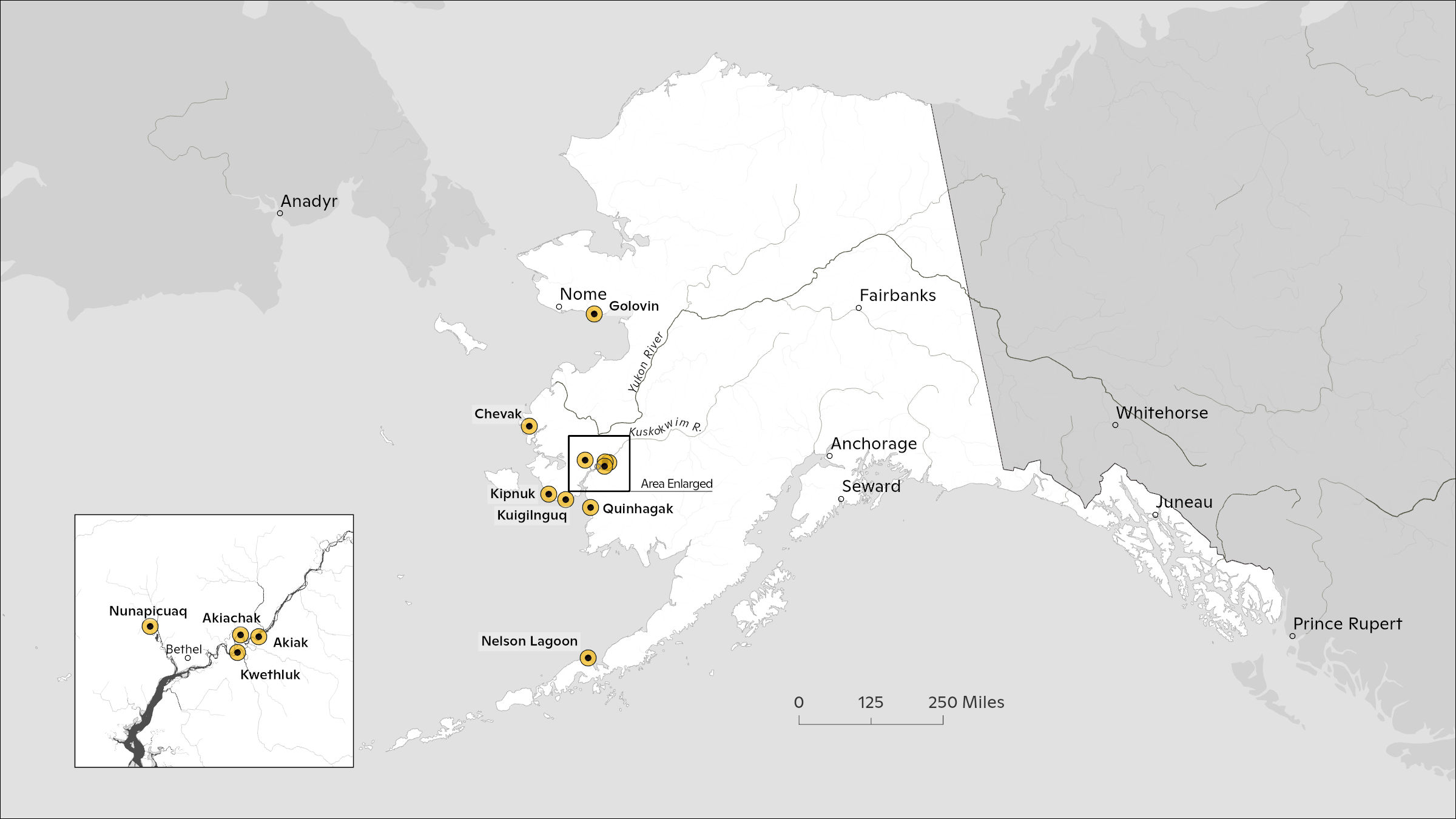

Left: IGAP Coordinator and Tribal Council President Angela Johnson from Nelson Lagoon presenting on the environmental threats and needs of her community. Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Right: Non-storm event flooding in Kuiqilnguq. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Speaking truth to power

The workshop kicked off with powerful community presentations by Permafrost Pathways Tribal partners from Akiachak, Akiak, Chevak, Chinik (Golovin), Nunapicuaq, Kipnuk, Kuigilnguq, Kwethluk, Nelson Lagoon, and Kwinhagak (Quinhagak). The community presentations laid bare the devastating climate impacts unfolding in their villages. Presenters described how Tribes are already taking action to mitigate these threats, and identified the most urgent adaptation needs for their communities to protect themselves and their traditional ways of life.

“It’s so important to be able to tell our own story and tell these agencies the issues that we are facing, what we’re dealing with on our own in our individual communities,” Environmental Coordinator and Tribal Council President for the Alaska Native Village of Nelson Lagoon, Angela Johnson told Alaska News Source. “I also think it’s important for them to see that there are so many different communities all along the state that are dealing with almost the same exact kind of problems, and there’s not enough resources out there right now and there’s not enough policies put in place right now to help protect us. We’re basically doing this on our own, fighting for competitive funding and not getting a lot of assistance from our government.”

Nelson Lagoon and Quinhagak (Kwinhagak) satellite imagery captured July 2021 courtesy of Maxar. Each Tribal partner was equipped with satellite imagery of their community to use as a visual aid during conversations with federal agencies about environmental changes Tribes are experiencing in their homelands due to climate change. Images by Greg Fiske/Woodwell Climate Research Center

Johnson emphasized in her presentation that the 10 Permafrost Pathways partner communities participating in the workshop are not the only villages in Alaska experiencing severe, ongoing impacts from climate change. 73 communities across the state face imminent threats from permafrost thaw, flooding, or erosion, and an estimated $5.5 billion worth of Alaskan infrastructure is expected to be damaged due to climate change this century.

The need for more streamlined inter-agency coordination in addressing adaptation needs is a challenge that both Tribes and agencies have acknowledged as an enduring barrier to progress. The new Voluntary Community-Driven Relocation Subcommittee under the White House National Climate Task Force represents an effort to overcome this issue. The working group will convene agency leaders in close collaboration with Tribal communities to facilitate pilot projects and programs applicable to climate-forced displacement. The adaptation workshop provided an essential opportunity for communities and agencies to collaborate face-to-face.

“One of the benefits of an event like this is that it allows focused conversations and ideas to advance faster than they would have if we hadn’t all been brought together in person,” said Jennifer Adleman, a community planner in Alaska for FEMA Region 10. “In that way, the workshop created a dedicated space and time to have these important community-led conversations, build upon them, and ultimately move them forward,” Adleman said.

“Community-Driven Relocation” panel with federal agency representatives. Photo by Tessa Varvares / Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School

Following community presentations, a panel of agency representatives from DOI, FEMA, Denali Commission, BIA, and the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), informed workshop participants about the efforts of the new working group, current opportunities for federal aid, how agencies can support community access to available resources, and what agencies are doing to improve their approach to climate adaptation and resilience.

“We’re hearing loud and clear the call for help. That people are focused on these issues, that they have been seeing them come for decades, and that there is a need for urgent action,” said Victoria Salinas, FEMA’s Associate Administrator for Resilience. “That’s part of the reason so many federal agencies have come together to be in conversation with these communities.”

Left: The Permafrost Pathways research team speaking with representatives from Nunapicuaq during community roundtable discussions.

Right: Morris Alexie describing environmental change happening in Nunapicuaq to the Alaska Institute for Justice’s Ben Baldwin and Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Sue Natali in Alaska this summer.

Photos by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Co-production of knowledge and community-based monitoring—Permafrost Pathways leads by example

Permafrost Pathways helped facilitate these conversations around adaptation and relocation. The project is working closely with Alaska Native partners and government agencies to identify the elements of a successful relocation approach, including the community relocation decision-making process, identifying and choosing relocation sites, government resources that can facilitate climate resilience, and the policy-level barriers that prevent communities from accessing them.

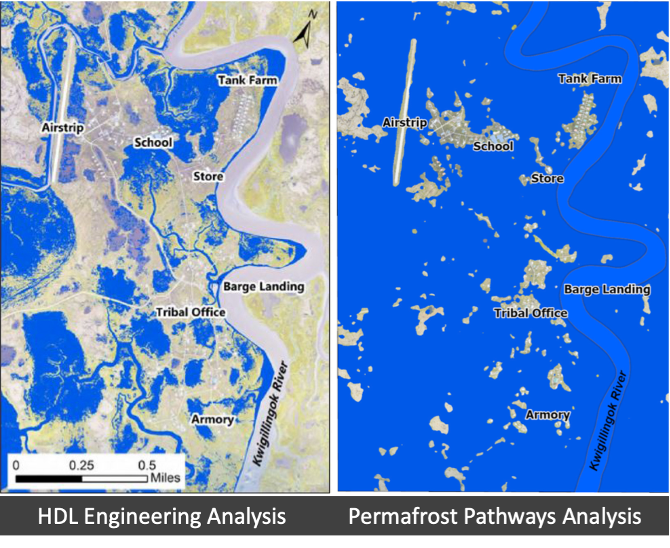

Left: A flood map of Kuigilnguq produced for a hazard report that underrepresents the extent of non-storm flooding in the community (left) next to a flood map created by Permafrost Pathways with community input.

Right: Greg Fiske and former Tribal Liaison Gary Evon co-producing the new flood map that more accurately represents the severity of non-storm event flooding in Kuigilnguq. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

One of the most important themes of this work is the co-production of knowledge. A Convergence Science panel during the workshop—moderated by Ben Baldwin, Climate Justice Tribal Liaison Director at AIJ and including Tribal Liaisons Darren John from Kuigilnguq and Morris Alexie from Nunapicuaq, AIJ’s Dr. Bronen, and Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Sue Natali—highlighted how Permafrost Pathways scientists and Alaska Native communities are working together to assess the environmental impacts of climate change in partner communities. Indigenous Knowledge and on-the-ground observations of permafrost thaw, flooding, and erosion are integrated with western science to inform adaptation decision-making.

“We are grateful and feel very lucky and gracious,” Alexie said. “Nunapicuaq would not be where we are today without the advice from Permafrost Pathways.”

While Permafrost Pathways is providing support, the project’s Alaska Native community partners are leading this unprecedented work and guiding federal agencies in the process. The ongoing Indigenous-led efforts in Alaska not only include developing and implementing responses to adaptation needs, but also designing a climate adaptation toolkit that will be broadly applicable to communities across the Arctic and ultimately influencing legislation and policy change.

Patricia Cochran (right) moderating the Alaska Native youth and Elder Q&A panel. Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Empowering the next generation of Alaska Native climate leaders

The workshop also featured a youth and Elder panel, moderated by Permafrost Pathways partner and Executive Director for the Alaska Native Science Commission, Patricia Cochran—an Inupiaq Elder born and raised in Nome, Alaska who has been researching climate change and working with and advocating for Alaska Native communities for decades. The panel offered a special opportunity for Alaska Native youth to learn from Elders who shared their experiences growing up on the land—describing how much it has changed in their lifetime alone and how young people in their communities can contribute to the fight against climate change.

Many Alaska Native communities have been observing permafrost thaw and other environmental changes in their villages over the span of generations. Elders hope to pass their intimate knowledge of the landscape and how it has changed over the years on to younger generations to see their work toward climate justice and community resilience carried into the future.

Cochran shared the importance of Elders empowering the next generation of community leaders, but acknowledged the unique challenge of emotional distress on both older and younger generations that comes with bearing witness to catastrophic environmental change in your homelands and grappling with the existential weight of an uncertain future.

“I have gone beyond hope. I have to instill belief,” Cochran said about inspiring and motivating Alaska Native youth to carry this work forward. “Belief that things can change and that we will survive.”

Satellite imagery of Kipnuk and Chinik (Golovin) captured July 2021 courtesy of Maxar. Satellite imagery is an important tool used by Permafrost Pathways researchers and Alaska Native community partners for environmental monitoring and adaptation planning. Images by Greg Fiske/Woodwell Climate Research Center

The road ahead is paved with cautious optimism

From the hard work of two intensive days spent sharing information and collaborating on difficult topics, many departed feeling optimistic about the future, hoping to build on the momentum from the workshop. Continued communication between government agencies, scientists, and Alaska Native communities will be critical for the work that lies ahead.

“Our communities are on the frontlines of climate change. Our land is falling apart and our people are doing everything we can to maintain our sense of self, to maintain our sense of community, to maintain our cultures, our language, our ways of life. It’s exhausting,” Baldwin said. “I know these topics are not easy to think about, but they are even harder to live through. Listen to our people. Hear our stories. Work together with us so our people can be kept safe.”

Go to top