Redefining Arctic research with equity at the center

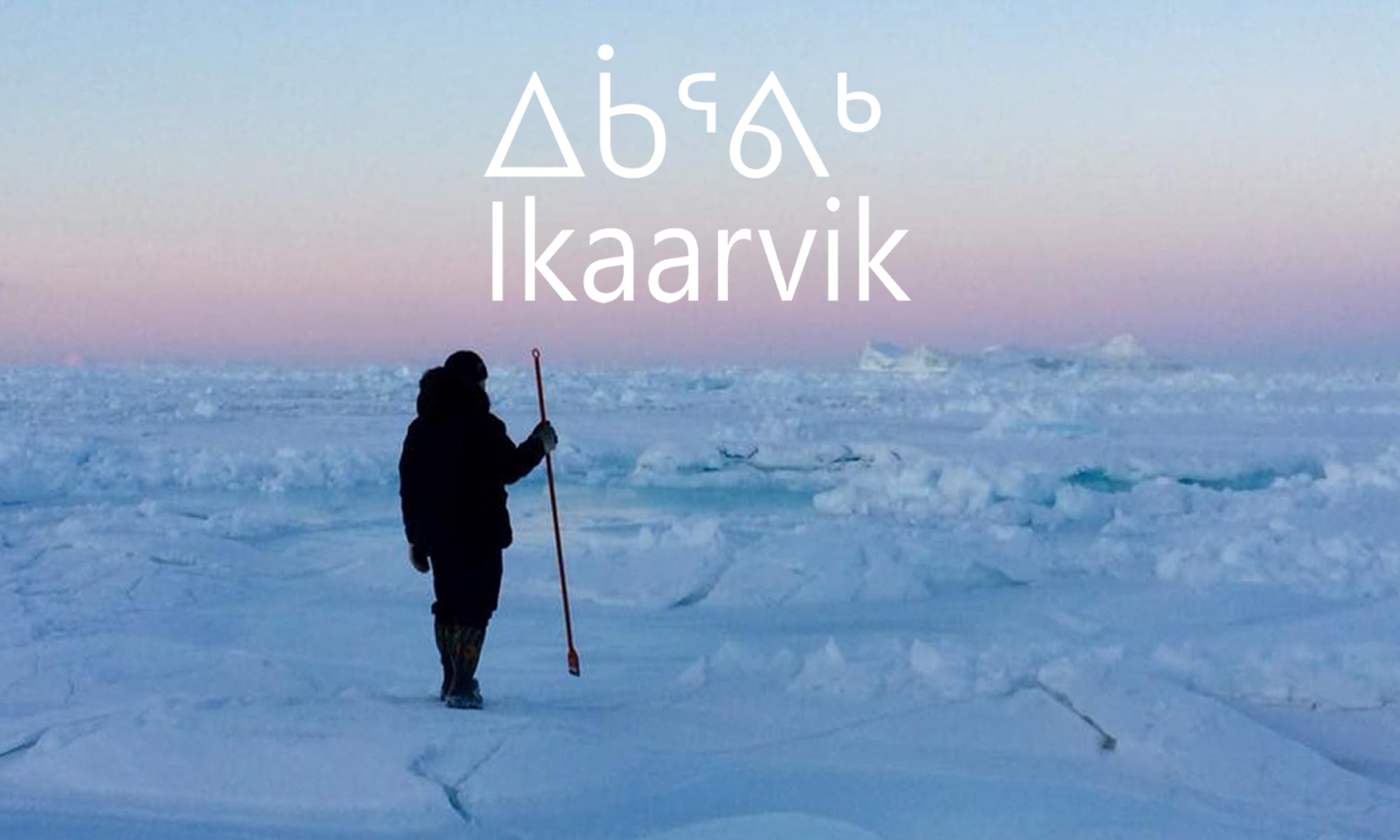

Sue Natali and Morris Alexie examine a map during a community visit to the Alaska Native Village of Nunapicuaq. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Communications Lead, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Indigenous leadership and equitable partnerships must determine the future of Arctic science.

In 2018, a group of Inuit youth stood before a scientific crowd at the annual ArcticNet conference in Ottawa, Canada. They spoke in Inuktitut—and observed the faces of the largely Western scientific crowd quickly turn to confusion.

For Indigenous communities in the North, the feeling of exclusion in a Western scientific space is commonplace. Researchers arriving in the Arctic often approach communities with very little consideration of linguistic barriers, historical context, or cultural differences. By flipping the script on the researchers, the Inuit youth delivered a clear message: Arctic research has an equity problem.

For too long, scientists have flown into Northern communities to collect samples, data, or stories, and flown out again with little trace of collaboration, benefit-sharing, or even communication with the people living there—whose lives and lands make the research possible. Today, that approach is being challenged. Indigenous Peoples are asserting their expertise, sovereignty, and rights to not only be consulted in but lead the very research that affects their present and future—ushering in a new era of Arctic research.

Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), Nunavut. Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic science’s history of harm

For generations, the North has been a target of colonial interests and resource exploitation. These same colonial dynamics have been replicated in the realm of research, influencing who sets the agenda, whose voices are heard, and whose knowledge is considered valid.

“Researchers come from outside into our region, and there is just this chasm that isn’t able to be bridged because of the communication—or the lack of it,” says Corina Qaaġraq Kramer, an Iñupiaq leader from Kotzebue, Alaska, and co-founder and CEO of Respectful Research, an Indigenous-led organization dedicated to transforming research relationships in the North. “There’s a lack of understanding on both sides, really, because of the multiple decades—centuries—of colonialism and the damage that was done.”

There is also a pervasive myth that the Arctic is largely an uninhabited wilderness, when in fact it is home to diverse Indigenous Peoples—including the Yup’ik, Athabaskan cultures, Iñupiat, Alutiiq, Gwich’in, Inuit, Inuvialuit, Sámi, Nenets, Khanty, Mansi, Evenk, Chukchi, and Kalaallit—who have lived on these lands for millennia. Their knowledge systems and culture are deeply tied to the land and water, yet Western research has historically ignored them.

Indigenous Peoples of the Circumarctic. Map by Christina Shintani / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“The other thing I always tend to ask people coming to our community, how much time, effort, money, and studying have you done to get to the position that you’re in now?” said Kramer. “How much time did you take to learn your expertise? And then I’ll ask, how much time have you put into getting to know the Inupiaq people of Northwest Alaska? A big fat zero for the most part.”

This inequity is entrenched in the structures of modern Arctic research, which run parallel to colonial extraction: data, insights, and prestige flow to institutions and outsiders. When research does find its way back to communities, it’s often presented using unfamiliar languages or Western scientific jargon that is not easily accessible.

“Even when researchers do give us results, they’re giving us all this information—but we don’t know what any of it means,” said Michael Milton, an Inuit youth leader and Senior Coordinator with Ikaarvik, a youth-led initiative in Nunavut that aims to bridge the gap between Western science and Indigenous Knowledge and cultural values in the Arctic. “And with the language translation, the interpretation may somehow be missed in both cases, from English to Inuktitut and from Inuktitut to English, and the cultural differences in between.”

Top: Michael Milton of Ikaarvik and Patrick Murphy at the research site in Mittimatalik. Photo courtesy of Michael Milton / Ikaarvik.

Bottom: Corina Kramer and Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq in Kotzebue, Alaska, teaching their Effective Community Engagement course. Photo courtesy of Corina Kramer / Respectful Research

Indigenous leaders reshaping Arctic research

To combat extractive research, Indigenous leaders are demanding not just inclusion, but a transformation of the research process itself. A growing movement led by Arctic Indigenous researchers, youth, and communities at large is reclaiming power and reshaping the research process to center equity, respect, and self-determination. This movement is more than a correction; it is an invitation to transform Arctic research into something accountable, reciprocal, and just.

Kramer, alongside her sister and Respectful Research co-founder, Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq, spent years studying conflict between researchers and communities and was able to identify best practices for effective community engagement, which grew into their training course of the same name.

Respectful Research logo. Image courtesy of Respectful Research LLC.

According to Kramer, a respectful research framework involves research practices that are not only scientifically robust but also support Indigenous leadership, youth engagement, and self-determination in research. From agenda setting and data governance to dissemination and benefit-sharing, communities should not only be consulted, but also involved in leading the research happening on their lands. She and Itchuaqiyaq also call for a shift toward research as a tool for cultural revitalization, economic development, and Indigenous climate resilience, rather than academic advancement alone.

Top: Effective Community Engagement course postcards. Photo courtesy of Corina Kramer / Respectful Research LLC

Bottom: Respectful Research webinar with ARCUS. Photo courtesy of Corina Kramer / Respectful Research LLC

“There are a lot of people doing really great work, but there are missed opportunities all over the place,” said Itchuaqiyaq. One example, she says, could be training community members to be field researchers, which would help build scientific capacity within communities and facilitate sample collection.

Itchuaqiyaq is also the Founding Director of the Center for Sustainable Engagement in the Arctic at Virginia Tech University, which she created to support the shift towards justice and equity in Arctic research.

“The center is really born out of the experiences that Corina and I have had together and thinking about how to institutionalize this, because there needs to be institutional support for the types of systemic shifts that we want to see,” said Itchuaqiyaq. “I want to help us create enabling structures for really intentional community engagement and to harness the capacity and expertise that already exists in communities.”

Organizations like Ikaarvik are also bringing Arctic youth into the conversation. Meaning “to bridge,” Ikaarvik provides training, mentorship, and leadership development to help youth identify and act on local research priorities, while connecting researchers more meaningfully with the communities in which they work.

“As youth, we are in a very unique position to understand and learn what we can do for our future, for our community, and for ourselves,” said Milton. He hopes that youth will become inspired to get more involved in local research as a means of career advancement, but more importantly, to also see themselves as leaders who can create meaningful change for themselves and for their communities.

Video: Ikaarvik photo slideshow.

In Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), Nunavut, Inuit youth have led workshops with visiting researchers to explore ScIQ—a model developed by Ikaarvik that combines Western science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (knowledge) and values. ScIQ treats both as legitimate ways of knowing and explores how they can inform and enrich one another. During the workshops, youth and researchers co‑develop research agendas, forge meaningful partnerships, and ensure that the results are of community-defined value.

“Once you get down to truly understanding each other, taking that extra time to learn from each other, things just snowball into incredible conversations, incredible results,” said Milton. “And I think that is like the true spirit of Qaujimajatuqangit and how we’ve done it so well for so long. It’s a bridge. It goes both ways. We have to understand each other.”

Top: Ikaarvik and Permafrost Pathways hosting an information table at the food co-op in Mittimatalik, Nunavut. Photo by Shelly Elverum / Ikaarvik

Bottom: Kramer and Itchuaqiyaq (far right) with session participants during Arctic Circle Assembly 2024. Photo courtesy of Respectful Research LLC

Equitable research benefits everyone

An equitable approach to research is critical to the success of Arctic science. Indigenous Knowledge holds long‐term observations and holistic ecological insights that Western science lacks. Research that doesn’t integrate that knowledge often misses crucial phenomena, misinterprets local systems, or yields less useful—and thus less impactful—findings.

“It’s to the detriment of everyone, because whatever you’re doing, whatever data you’re collecting would be so much better if you had input from community experts,” said Dr. Susan Natali. Natali is a Senior Scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center and Project Lead for Permafrost Pathways, whose team is taking a more equitable and human-first approach to Arctic research. “It’s the right thing to do, it’s the human thing to do, and it will make your work more relevant, more accurate, and most importantly, more equitable and just.”

When it comes to equitable and ethical Arctic research, Permafrost Pathways’ goal is to lead by example. For the project’s community-led adaptation work, Alaska Native community partners set the priorities based on their needs and guide researchers along the way. Before selecting a field site on the science side, researchers on the project will first connect with communities whose lands the intended site is located within to begin establishing a mutually beneficial partnership rooted in community-defined values. The project has been collaborating with Respectful Research and Ikaarvik to ensure that the science being conducted on the project is not only inclusive of Indigenous Knowledge, but also centers community involvement.

Patrick Murphy and other members of Permafrost Pathways with Ikaarvik at a carbon flux tower site in Mittimatalik, Nunavut. Photo by Shelly Elverum / Ikaarvik

“We are scientifically telling a story about how climate change is affecting permafrost,” said Patrick Murphy, a Field Technician for Permafrost Pathways at Woodwell Climate. “But without any sort of input or involvement from the people who live there, it’s just not a complete story.”

Murphy works on the project’s carbon flux monitoring team. For him, the partnerships with Respectful Research and Ikaarvik helped him understand that for science to be impactful at all, local support and legitimacy matter. Research that disregards community priorities or does not include community voices risks mistrust, resistance, or rejection.

“You can’t just treat community engagement like an item on a checklist. You’re not just checking off a box,” said Murphy. “You are starting your project with community engagement at the center and building your project around that.”

Shifting research frameworks towards more equitable approaches can be difficult, sometimes evoking defensive reactions from long-time Arctic scientists. But Shelly Elverum, Ikaarvik’s Senior Advisor of Community Partnerships and Communication, believes equitable approaches don’t have to be intimidating or scary.

“Ikaarvik’s approach has always been to not make people feel ashamed for what they don’t know, and then to tackle a lot of the discomfort with humor, because it works both ways,” said Elverum. “I mean, communities are also deeply uncomfortable with researchers that would fly in and make demands and have schedules and do all these things that were very uncomfortable. So rather than stressing out about it, let’s have a couple of laughs.”

Humility and a willingness to learn are essential in shifting Arctic research approaches, according to Research Scientist and Climate Justice Specialist, Dr. Nigel Golden, who leads the Polaris Project—an immersive undergraduate program for aspiring Arctic researchers.

Top: Ikaarvik and Permafrost Pathways teams in Mittimatalik, Nunavut. Photo by Kyle Arndt / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Bottom: Dr. Nigel Golden working with a student as part of the Polaris Project, which has been implementing community engagement as a mandatory part of the program. Photo by Andre Price and Onjalé Scott Price

“The time is always now, and no one expects you to do it perfectly,” said Golden. “We are professional learners. It’s really about prioritizing it, tapping in, and finding the time to do the work.”

Natali says she views the shift to equitable research as a journey of knowledge, one where researchers grow from their mistakes, try again, and do better next time.

“Every single time I go into a new community or even a community that I’ve been to before, I go on that journey again and I learn something new every time,” said Natali. “I think it involves a lot of listening and a lot of learning, and always seeing myself as a learner, being humble, and not thinking that I have all the answers. To learn, to be better, to create change, you have to allow people to make mistakes, and I’m seeing more of that growth happening now.”

Top: Milton with Ikaarvik and the Permafrost Pathways team at a carbon flux tower site in Mittimatalik, Nunavut. Photo courtesy of Michael Milton / Ikaarvik

Bottom: Kramer leading a traditional blanket toss activity at Arctic Circle Assembly 2024. Photo courtesy of Repectful Research LLC

A new era of Arctic research, ‘Who else can do it but us?’

Mindsets are beginning to change as the benefits of equitable Arctic research become more pronounced. In the U.S., the National Science Foundation (NSF) announced a new rule in 2024 that requires Tribal approval for projects impacting Indigenous interests. This marked a turning point in acknowledging that free, prior, and informed consent must be a baseline—not an afterthought.

“We have seen a massive shift,” said Milton. “There are organizations being built, left, right, and center, all across Nunavut, and there are even funding organizations that require you to work with Inuit.”

Even for more seasoned career professionals, equitable research is increasingly becoming a priority in their work.

Video: Arctic Circle Assembly 2025 where Kramer, Itchuaqiyaq, Natali, and Golden participated in the session, “Reimagining Arctic Research: Centering Indigenous Knowledge, Equity, and Justice.”

“I’m seeing a lot more curiosity from our more experienced colleagues as well, acknowledging that they don’t know what to do or where to begin, but they are curious, and they are leaning into that curiosity,” Golden said. “I think it’s those small steps that matter. Curiosity is a really good place to start.”

At its best, Arctic research can be a force for good: developing equitable solutions to rapid Arctic change with Indigenous communities at the helm. But only if we stay the course and make equitable and ethical approaches a priority.

“Respectful research is important because it’s just and it’s right, and it’s equitable, but it’s also important if you want to be a good scientist, and I think that understanding is critical to address the complex impacts of climate change,” said Natali.

Top: Natali with Morris Alexie and Jackie Dean in Nunapicuaq, Alaska. Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Bottom: Corina Kramer. Photo courtesy of Corina Kramer / Respectful Research LLC

Kramer hopes that through this cultural shift in research, Arctic Indigenous communities will also reclaim their expertise and confidence.

“What I hope to see the most, actually, is that our communities become who we used to be, and believe in who we are,” said Kramer. “We have to believe. We have to understand that we have survived and thrived in the harshest environments in the world for thousands of years.”

To Golden, pursuing justice and equity is a moral obligation to change science for the better.

“This is what it means to be a scientist in the 21st Century,” said Golden. “This is what it means to learn in the 21st Century. We acknowledge this history, we acknowledge that these legacies exist, and we acknowledge that there are better ways to do science.”

And when it comes to those better ways of conducting science, who better to lead the way than Arctic communities themselves?

“Who else can do it but us?” said Kramer. “Who else can do it? Are you going to develop something for Indigenous rights or communities that serve our needs, and listen to and work toward the goals and the priorities of our communities? Who else can do this better than us?”

In memoriam

In memory of Peter Inootik (1989-2025) of Mittimatalik ᒥᑦᑎᒪᑕᓕᒃ (Pond Inlet), who graciously gave us his time, guidance, and friendship. We are forever grateful.

Go to top