Thawing ground, frozen systems: Erosion case study reveals U.S. climate policy gaps in Chevak, Alaska

Cev'aq, Alaska. Photo by Darcy Peter / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Lynn Heller M.A.Arctic Policy Research Assistant, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Cup’ik village confronts rapid land loss from permafrost thaw and erosion, urging federal action

In the Alaska Native Village of Cev’aq (Chevak), permafrost thaw is contributing to the rapid erosion and land destabilization beneath critical community infrastructure. A culvert installed to manage spring flooding, which has intensified as the land around has thawed, has inadvertently redirected water towards land that was already eroding, accelerating degradation and putting homes and people at risk. Despite the clear and impending threat, a lack of clear jurisdiction and outdated disaster frameworks have prevented governmental agencies from adequately addressing this issue.

Tiffany Windholz and Aurora Taylor survey the erosion with Cynthia Paniyak and other community members.

Photo by Darcy Peter / Woodwell Climate Research Center

In partnership with Cev’aq, Permafrost Pathways has produced a case study that details the challenges from permafrost thaw, erosion, flooding, and other climate impacts that the Cev’aq community is living through with limited institutional support. The study reveals how federal and state systems often fail to recognize the urgency of gradual, compounding environmental threats, and how this failure leaves Tribal communities to bear the disproportionate impacts from climate change.

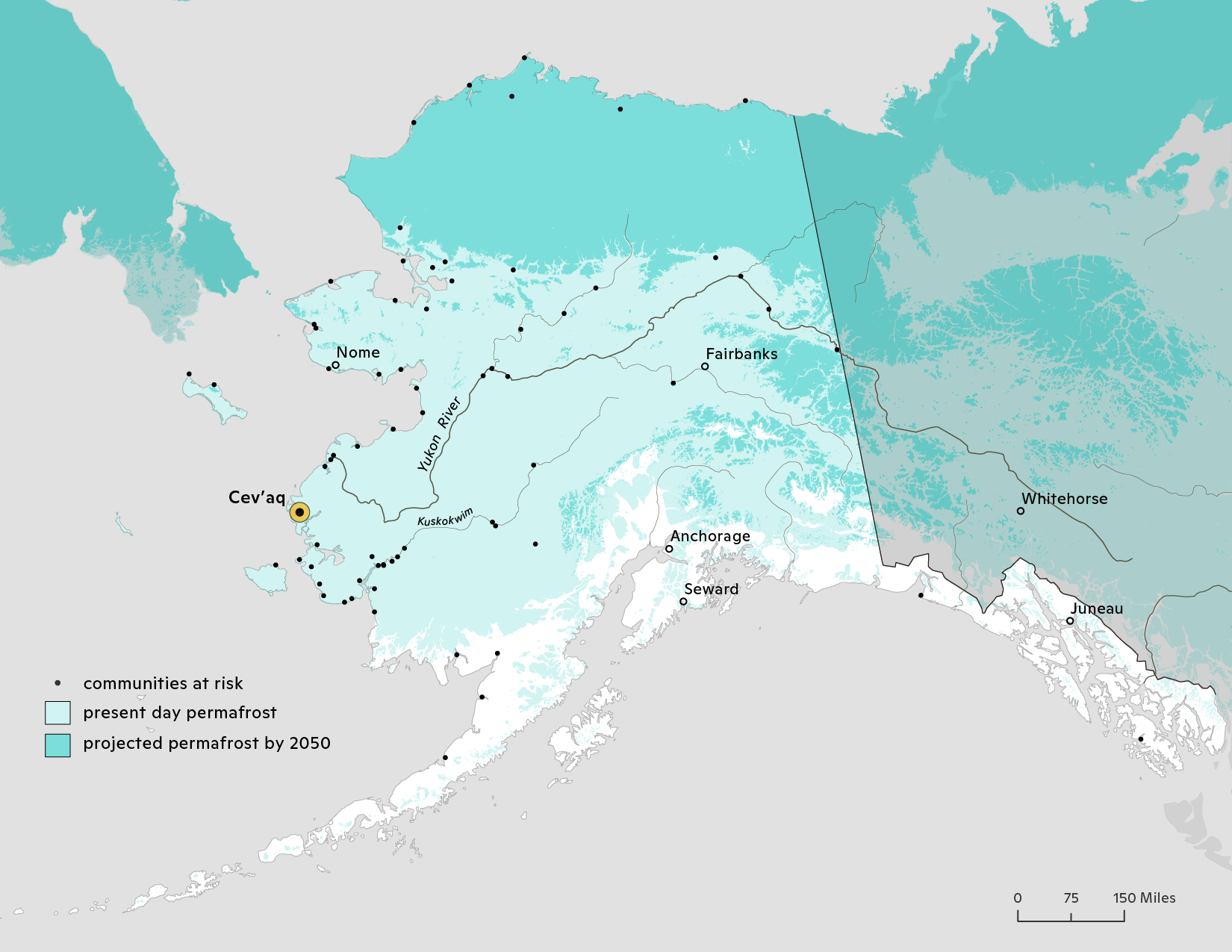

Cev’aq is a Cup’ik village that sits on the Ninglikfak River in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Across this region, warming temperatures have triggered a compounding hazard known in the Yup’ik language as usteq—catastrophic ground collapse. Permafrost thaw destabilizes the ground beneath community infrastructure. When paired with changes in water flow, it can trigger sudden and irreversible land loss. It’s a process now acknowledged in Alaska’s hazard mitigation plans, but largely overlooked in federal disaster law.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

In 2021, a culvert installed to manage thaw-related flooding inadvertently exacerbated erosion, intensifying land collapse near homes. By summer 2024, Cev’aq had lost more than seven feet of ground in some places, putting many structures at risk, including a culturally important community maqivik, or steam house.

“The elevated dirt roads and placement of the culvert have diverted the majority of the drainage to the southwest end of town, where the runoff from the culvert has created erosion from the bluff edge between two residential homes,” Reggie Tuluk, Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison for Cev’aq, said in the case study. “New placements of culverts have also created standing snow melt water to flood homes and properties in the center of town along the road that goes towards the west end of town.”

Extension erosion from August 2023 to August 2024.

Photos by Sue Natali and Darcy Peter / Woodwell Climate Research Center

The crisis in Cev’aq is not a sudden disaster—it’s a slow and steady combination of landscape collapse shaped by climate change, inadequate infrastructure, and systemic gaps in federal and state emergency response. Unlike hurricanes or wildfires, the threats facing Cev’aq don’t fit the existing paradigms of federal disaster response. Existing laws, such as the Stafford Act, define disasters in sudden, event-driven terms, which allows threats like usteq to fall through the cracks. And while some federal programs can address slow-onset hazards without a federal disaster declaration, like the Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Emergency Watershed Protection program, their eligibility criteria are vague and not designed for an Arctic context. In Alaska, where erosion and permafrost thaw create complex landscapes, something like a watershed can be hard to define, preventing communities from accessing support. Despite multiple federal and state assessments over the last decade warning of Cev’aq’s erosion risks, agency responses have been limited to temporary, isolated, and reactionary measures.

As a result, the burden of addressing these hazards has fallen on the village itself.

Reggie Tuluk measuring the depth of the eroding culvert.

Photo by Darcy Peter / Woodwell Climate Research Center

In 2023 and 2024, Cev’aq residents and partners—including Permafrost Pathways and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium—documented permafrost thaw and erosion with field surveys, photos, and ground monitoring. Community members filled the eroding bluff with sandbags to temporarily mitigate the rate of erosion. Cev’aq worked with Engineering Without Borders at the University of Washington and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Region 10 to develop a plan and budget to adequately address the issue. The cost for a long-term solution was estimated at just over $6 million.

The village has applied for Congressional Directed Spending and a Tribal Climate Resilience grant to support a long-term fix. Federal and state agencies, including FEMA, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the State of Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, have the tools and expertise to help, but limitations within current frameworks prevent timely intervention. These agencies are generally restricted to responding only when erosion or flooding is directly tied to a state- or federally-declared disaster. The U.S. Government Accountability Office and the Denali Commission have both called for a unified federal response to climate threats in Alaska Native communities, but that unification has yet to materialize.

Sandbags were placed in the culvert as a temporary measure to mitigate erosion.

Photos by Jackie Dean / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“This erosion increases with each rainfall or spring melt, everyone really can see the impacts of permafrost thaw and how quickly it can increase with the amount of rain we’ve been getting the last few years,” Cynthia Paniyak, environmental coordinator for the Village of Cev’aq, said in the case study.

Cev’aq’s story is not only a warning, but a call to action. The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium estimates $4 billion will be needed over the next 50 years to protect existing infrastructure in environmentally threatened Alaska Native communities. And this figure only reflects current risks, not the new threats emerging each year. As climate impacts intensify, the cost of inaction is rising fast. The case study calls for policy reform “through the lens of justice, partnership, and long-term resilience” and advocates for strengthening policy responses to slow-onset and compounding climate hazards. Identifying barriers to coordinated emergency action and improving adaptation planning and disaster relief is necessary to support long-term resilience and the health and well-being of Arctic communities.

Go to top