Climate Adaptation Specialist Brooke Woods invited to speak at Mountainfilm 2025

Daily life in Rampart, Alaska. Photo by Keri Oberly.

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Woods joins Deb Haaland, Jade Begay, and other Tribal leaders to champion Indigenous Knowledge and expertise in land and water management

Brooke Woods, a Dlel Taaneets (Dene) advocate for Alaska Native fishing rights and Climate Adaptation Specialist for Permafrost Pathways at Woodwell Climate Research Center, will speak at the 47th annual Mountainfilm Festival in Telluride, CO. The prestigious event brings together stories, people, and ideas to inspire positive social change through film.

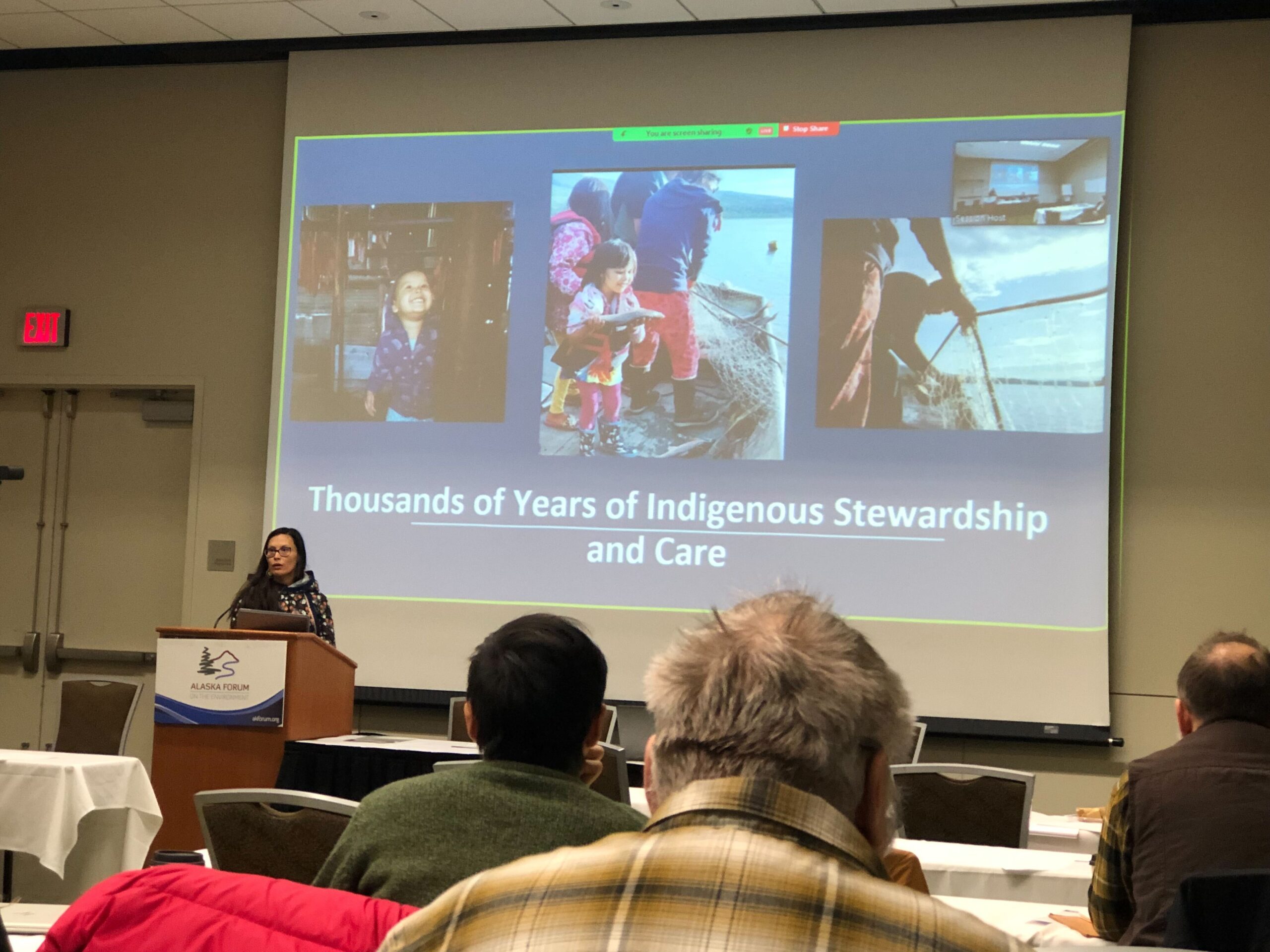

Brooke Woods speaking about the Alaska salmon crisis at the Alaska Forum on the Environment, where she received a standing ovation.

Photo by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

As part of the “Minds Moving Mountains” Speaker Series, Woods will join Indigenous leaders—including former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and climate policy expert Jade Begay—on the panel, “A New Era of Conservation: How Indigenous Leadership Is Reshaping What We Thought We Knew About Land Management.” The panel will focus on the movement to re-Indigenize conservation, exploring how Indigenous Knowledge, voices, and expertise are crucial in land and water management. The festival will also be screening “This is a Story About Salmon,” a short documentary film by Princess Daazhraii Johnson (Neets’aii Gwich’in), featuring Woods and other Alaska Native women advocating to save salmon and the future of their communities.

The village of Rampart, Alaska.

Photos by Keri Oberly

Woods is Koyukon Athabascan from Rampart, Alaska—a small fishing village that sits along the Yukon River and exclusively depends on king salmon and fall chum subsistence fishing to sustain their culture and community. However, the compounding impacts of climate change and the pressure put on salmon by commercial fishing and trawling industries are causing rapid species decline. Alaska Native Tribes are now facing complete closures to salmon fishing until 2030.

Woods has long fought to protect Indigenous subsistence fishing practices in Alaska. Through her work with the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Permafrost Pathways, and various academic and policy initiatives, Woods integrates Indigenous Knowledge and expertise with Western science to shape equitable Arctic climate and fisheries policy.

Cutting fish in Rampart, Alaska.

Photo courtesy of Brooke Woods.

As a mother, and scholar at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Woods continues to champion the rights and voices of Alaska Native communities, advocating for sustainable land and water stewardship rooted in traditional values. She has testified to the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, Board of Fisheries, Federal Subsistence Board, Yukon River Panel, and her work has been published in several journals, including The Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development; Ecology and Society; and the American Fisheries Society. She has also been quoted in major media outlets including USA Today, High Country News, Hakai Magazine, Anchorage Daily News, and Alaska Public Media.

Setting nets for white fish in Rampart, Alaska.

Photos by Keri Oberly.

In the excerpt below from Woodwell Climate, Woods talks about her approach to climate resilience for Rampart and other Yukon River communities.

Resilience is an uphill battle with a wildfire behind you

Woods’ hometown of Rampart, Alaska, is a small fishing village on the Yukon River. Here, Alaska Native residents practice a cyclical lifestyle, following the seasons to live off the land. Rampart, like many communities in interior Alaska—and across the Arctic—is feeling the impacts of the warming climate now.

The Arctic is one of the fastest-warming places on the planet, and as it heats up, permafrost, or perennially frozen ground, upon which many villages are built, is thawing. This can lead to erosion, ground collapse, and infrastructural damage. Woods’s role on Woodwell Climate’s Permafrost Pathways project is to use her policy expertise to help Tribal partners navigate the tricky landscape of federal and state agencies and funding, as well as uplift Tribal sovereignty.

Empty smoke houses and fish racks in Rampart, Alaska.

Photos by Keri Oberly.

On the Yukon River, one of the biggest concerns is the complete collapse of multiple salmon species. Salmon are suffering heat stress from increased water temperatures, changes in the marine environment, overharvest from bycatch in federal and state fisheries, and competition from hatchery-produced fish.

“We have not been able to fish for five years with an expectation that we will not fish for seven more, and that is a climate and cultural crisis.”

Losing access to these fish cuts off Tribes from a traditional cultural practice as well as a critical food source. Both state and federal agencies are involved in managing fisheries in Alaska, and while there are options for consultation, there is no deference to Tribes in decision-making.

Smokehouse in Rampart, Alaska.

Photos by Brooke Woods and Keri Oberly.

Additionally, the threat of permafrost thaw places Tribes in an emotionally challenging position. Community members must decide whether to relocate their villages or stay and shore up crumbling infrastructure, with little guidance or support from government agencies.

“There is no adaptation framework for the crisis Tribes are in when it comes to relocation. One big hope of this project and working with our Tribal liaisons is developing that [framework] in any stage. That would be a big success.”

The fight for deference, respect, and resources has not been an easy one. Woods compares it to escaping a wildfire to face an uphill climb. But her people’s history of resilience—of maintaining their connection to the land over 10,000 years in Alaska—gives her strength.

Woods family in Rampart, Alaska.

Photos by Keri Oberly.

“You get out of the wildfire, and you make your way up, and it’s a constant fight. Our ways of life are so connected to our ability to hunt, fish, and gather that Tribes are willing to continue this good fight. When it comes to advocating for our ways of life, our people are so humble and working tirelessly.”

A resilient Yukon River community looks like: Healthy salmon populations, stable permafrost, legal deference to Tribes in decision-making around natural resources, federal and state support for relocation, and continued traditional ways of life.

Read about other communities building climate resilience in this story from Woodwell Climate.

Go to top