Arctic Indigenous mapmakers are reclaiming the past, shaping their future

Maps bringing people together during a community trip to Chinik (Golovin), Alaska. Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost Pathways builds GIS capacity with Alaska Native communities, leverages co-produced maps for policy change

“What if you’re not on the map?”

Dr. Kelsey Leonard of the Shinnecock Indian Nation addressed this question to a room of Geographic Information System (GIS) professionals at Esri’s global mapping conference in 2023. Leonard, who uses maps to advance Indigenous water justice, asks this question to raise awareness about the absence of Indigenous land and languages in GIS tools. The removal of traditional place names in physical spaces, cartographic maps, and geospatial software often contributes to the erasure of Indigenous culture and history.

The Permafrost Pathways project, like Leonard, is working to change that.

The Native Land Digital App — a tool that aims to recognize Indigenous lands around the world to honor Indigenous resilience past, present, and future. Screenshot courtesy of the Native Land App.

Building Indigenous GIS Capacity in the Arctic

Due to dispossession and forced displacement caused by colonization, Indigenous People in the United States have lost nearly 99% of their land. While verbal and physical land acknowledgments aim to recognize this history of land theft and elevate the visibility of Indigenous Peoples as the land’s original and rightful inhabitants, another movement to decolonize place and space is gaining momentum: Indigenous mapmaking.

Nikolas Galanin’s “NEVER FORGET” art exhibit, a physical land acknowledgment outside of Palm Springs, California installed to raise awareness about the Indigenous Peoples who are the original stewards of the land.

Photo by Lance Gerber / Lance Gerber Studio

Permafrost Pathways has been working with Alaska Native partners to support this larger movement by building GIS capacity within communities. The project trains Tribal liaisons to use mapping tools and software through a long-standing partnership with GIS software provider, Esri.

“Tribal sovereignty is a huge priority for Permafrost Pathways,” said Darcy Peter, Woodwell Climate’s Arctic Adaptation Lead. “While providing GIS as a service to communities is meaningful and important work, we find a deeper value in building Tribal GIS capacity and sovereignty. Tribes have relied on outside entities for a multitude of necessary things, but I think it’s time for that to change. People who live in the community know what’s best for their people, their land, their way of life.”

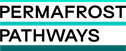

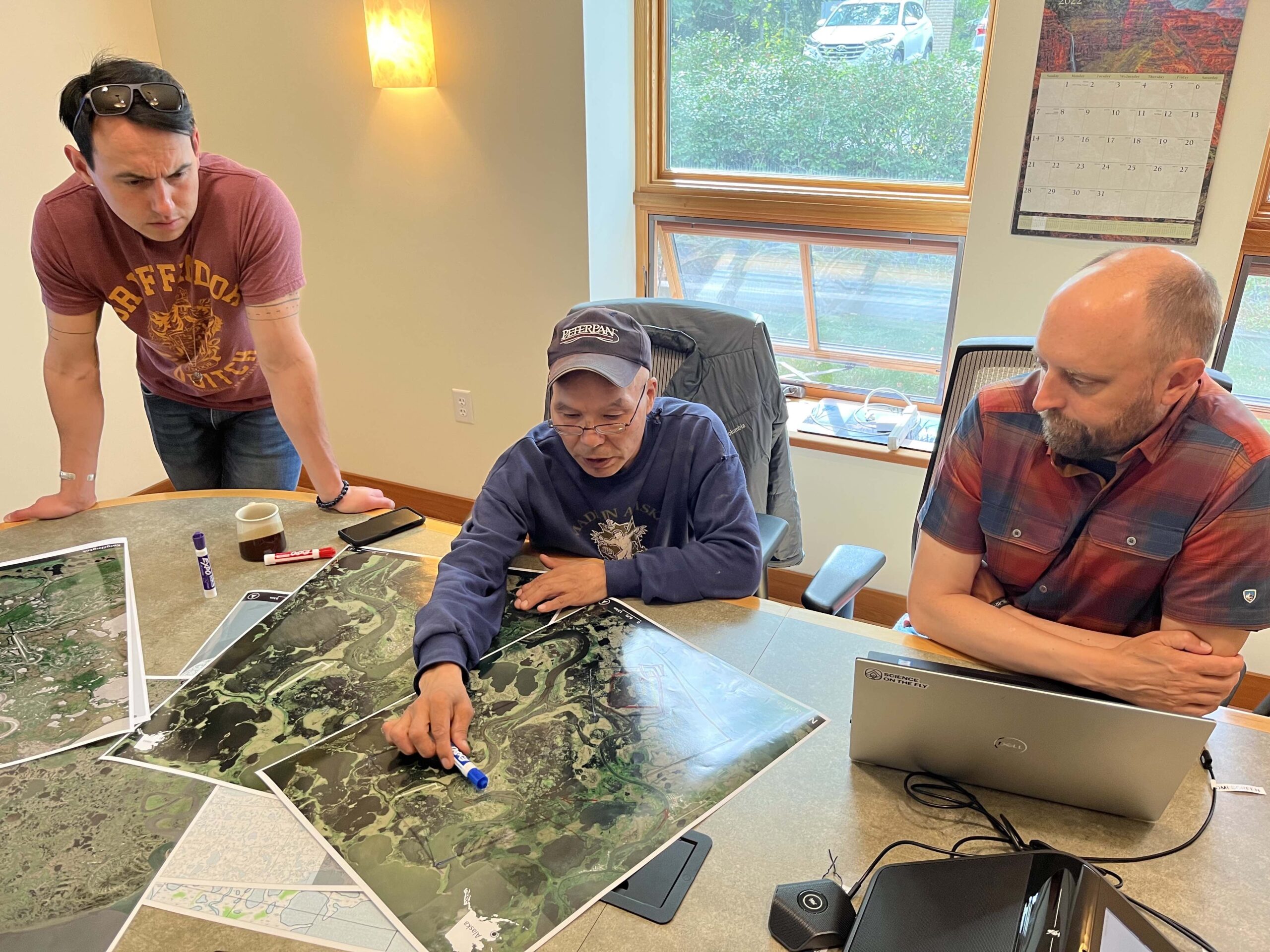

Morris Alexie sits with the Permafrost Pathways team telling stories about Nunapicuaq, which means “small tundra land” in the traditional Yup’ik language.

Photos by Sue Natali and Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

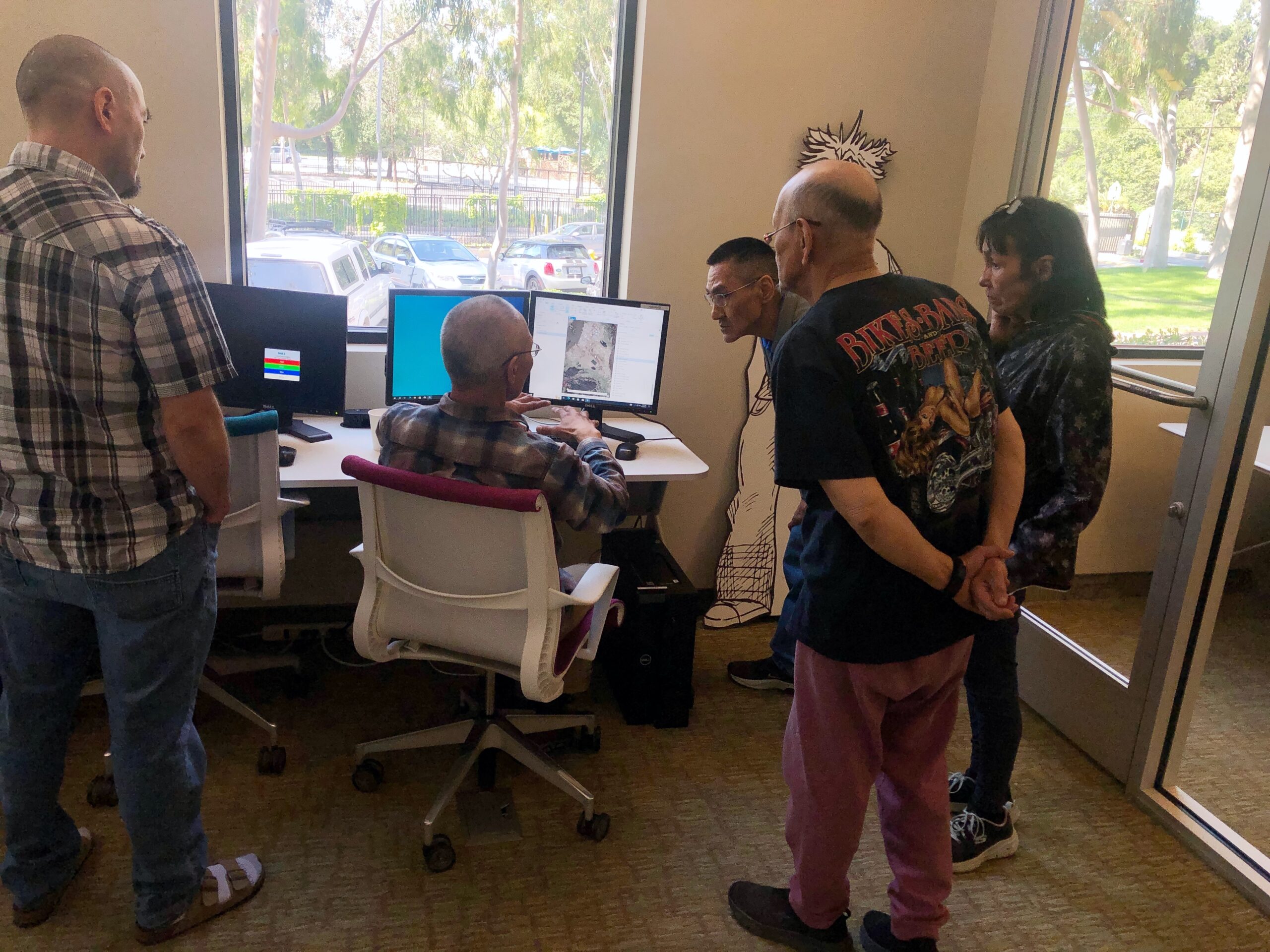

Earlier this year, Permafrost Pathways and Esri co-hosted a mapping workshop on Esri’s campus in Redlands, California with Alaska Native community partners from Akiaq (Akiak), Kuiggluk (Kwethluk), Nunapicuaq (Nunapitchuk), Kuigilnguq (Kwigillingok), Qipnek (Kipnuk), Cev’aq (Chevak), and Quinhagak (Kwinhagak).

The workshop included hands-on GIS training sessions and presentations about using geospatial data to map landscape change and support adaptation decision-making. Esri’s menu of specialized ArcGIS tools—including products like Survey 123 and ArcGIS StoryMaps—can also help community partners track storm impacts, collect environmental data, and share their own stories and observations of how climate change is unfolding in their villages.

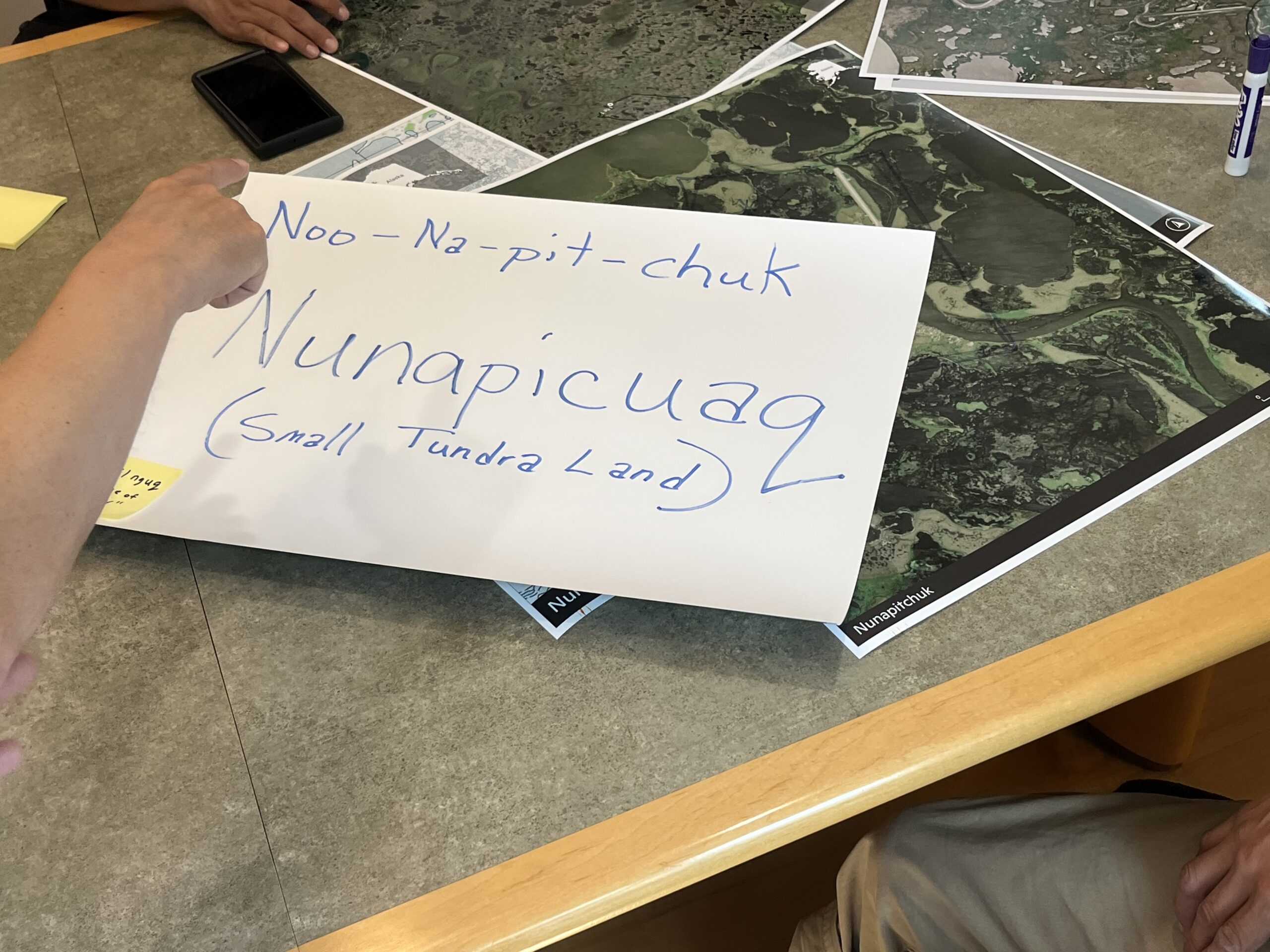

Alaska Native community partners working with local environmental data in ArcGIS during a hands-on workshop at Esri’s campus in Redlands, California.

Photos by Jessica Howard / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“Learning mapping and GIS skills is important to me and my community of Kuigilnguq because it helps us plan more accurately regarding our relocation efforts,” said Lucy Martin, Tribal Resilience Planning Assistant for Kuigilnguq. Martin uses Esri’s ArcGIS StoryMaps application to document local observations of environmental change and raise awareness about climate impacts in her village.

Expanding on what they learned at the workshop, Martin and Ferdinand Cleveland, former Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison from Quinhagak, attended the annual Esri User Conference in San Diego this summer. At the conference, they participated in additional GIS technical sessions and workshops. They also learned about how other Indigenous GIS professionals across the world are using Esri’s tools during the event’s Native Nations Summit.

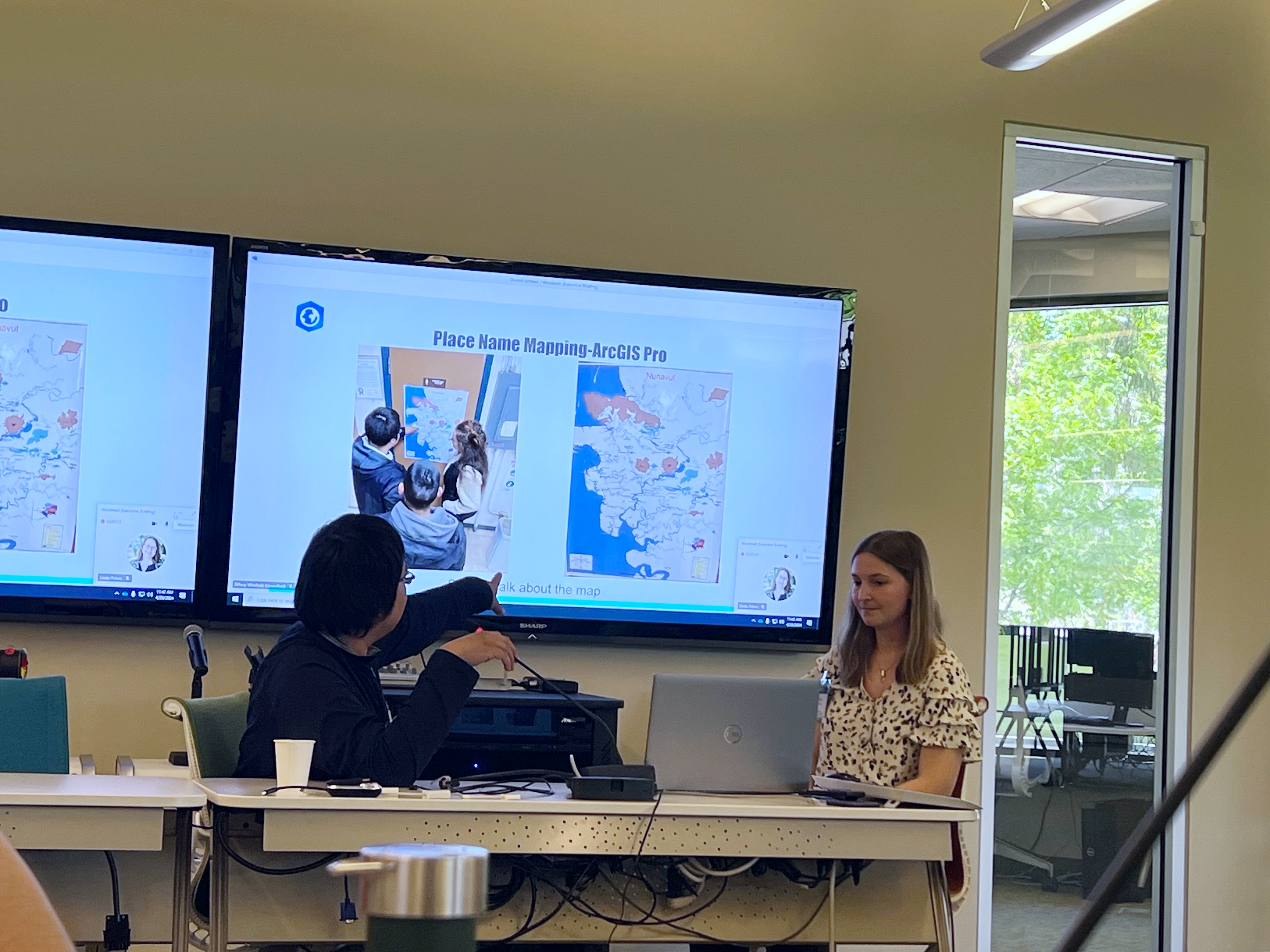

Top: Reggie Tuluk and Research Assistant Tiffany Windholz talk about Indigenous place name mapping in Cev’aq.

Bottom: Martin Andrew of Kuiggluk presenting his StoryMap during the GIS workshop.

Photos by Esri staff

Many Alaska Native community partners, like Cev’aq Tribal Liaison Reggie Tuluk, are also using Esri’s software to create Indigenous place name maps of their communities in their Native languages. Tuluk said the GIS workshop was an “amazing and educational experience.” He is also hoping to engage the youth in Cev’aq to get more involved in GIS.

“I look forward to getting more in-depth education in learning mapping and GIS skills,” said Tuluk.

Like Tuluk, Nunapicuaq Tribal Liaison Morris Alexie also plans to involve youth from his community, especially when it comes to archiving cultural lifeways and learning Yugtun, the traditional Yup’ik language.

“There are place names in certain areas of our community that are not used anymore,” Alexie said.

He hopes to use StoryMaps to inspire youth to combine modern technology with educational storytelling to keep Yugtun alive for future generations.

Woodwell Climate’s Senior Geospatial Analyst Greg Fiske, who has been working with Esri and Alaska Native community partners for years, found it especially rewarding to see these collaborations come to fruition at the GIS workshop and Esri User Conference.

“The group was able to come together, and it was immediately clear that there are many ways shared GIS technology can support climate-related challenges in the Arctic,” Fiske said.

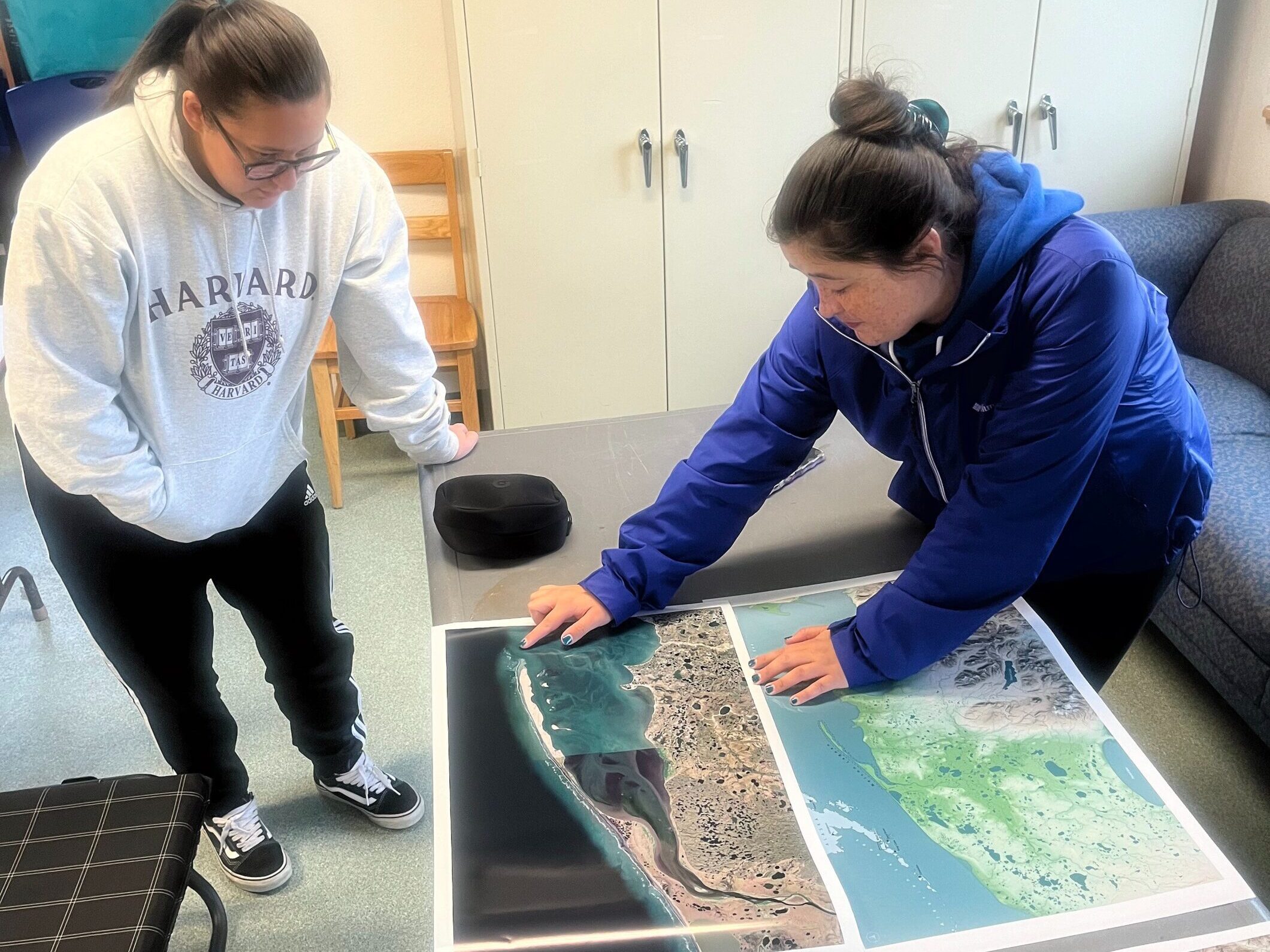

Permafrost Pathways Research Assistant Jackie Dean and Cev’aq Tribal Liaison Reggie Tuluk using GPS to co-create maps that illustrate the extreme erosion impacting community infrastructure in Cev’aq.

Photos by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

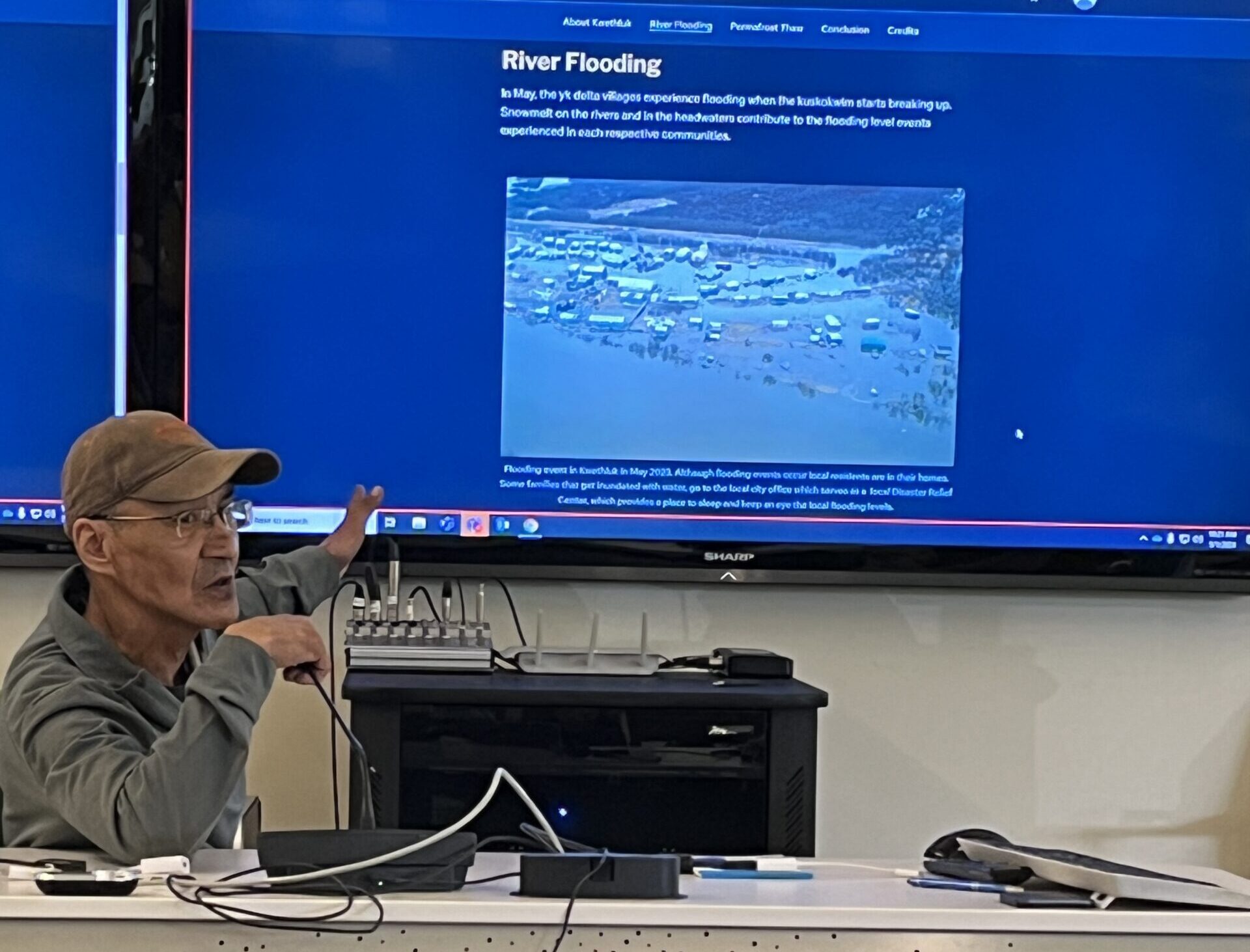

Co-producing maps to track environmental change

Permafrost Pathways is also working with Alaska Native community partners to co-produce maps of the changing landscape in and around their communities. In villages like Cev’aq and Akiaq, rapid erosion caused by permafrost thaw and flooding is a major threat to community infrastructure and safety. Co-creating maps that illustrate these threats helps to inform community disaster planning and response, as well as supplement environmental assessment reports and grant applications.

In April 2023, Fiske worked with Gary Evon, a former Permafrost Pathways Tribal Liaison, to correct a map from a community hazard assessment report conducted by an external engineering firm that had inaccurately captured the severe tidal flooding in Kuigilnguq. Evon used high-resolution satellite imagery to identify unflooded areas during high tide. He and Fiske then plotted those areas using GPS to co-produce a map that better reflected the extreme tidal inundation occurring regularly across the community.

Gary Evon and Greg Fiske co-producing a flood map of Kuigilnguq.

Evon and Fiske’s co-produced flood map illustrates the importance of including lived experiences and local observations from community experts in geospatial representations of environmental hazards. Maps created without community input lack important insight into the bigger picture and often underrepresent the true extent of environmental threats and community adaptation needs.

Animated flood map created by Evon and Fiske.

Photo by Sue Natali / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Maps inform Arctic policy responses

Co-produced maps also have the potential to influence policymakers. By combining Indigenous Knowledge and community observations with Western science, co-production communicates the needs of communities more accurately and powerfully than science alone.

“Maps are key for storytelling,” said Senior Scientist and Project Lead Sue Natali. “A good map helps you navigate your local space. They can also change people’s minds, they can shift policy.”

Morris Alexie during congressional meetings with Rep. Peltola’s office (top) and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (bottom) in Washington D.C.

Photos by Tierney Cross

Maps have the power to transcend language, cultural, and disciplinary boundaries that often present communication barriers. For policymakers from the contiguous United States who aren’t regular witnesses to rapid environmental change in the north, maps are paramount to understanding the impacts of Arctic permafrost thaw and realizing the urgent need for more federal support for climate adaptation and mitigation. Additionally, maps can also help these policymakers understand the potential impact of their legislation and decision-making.

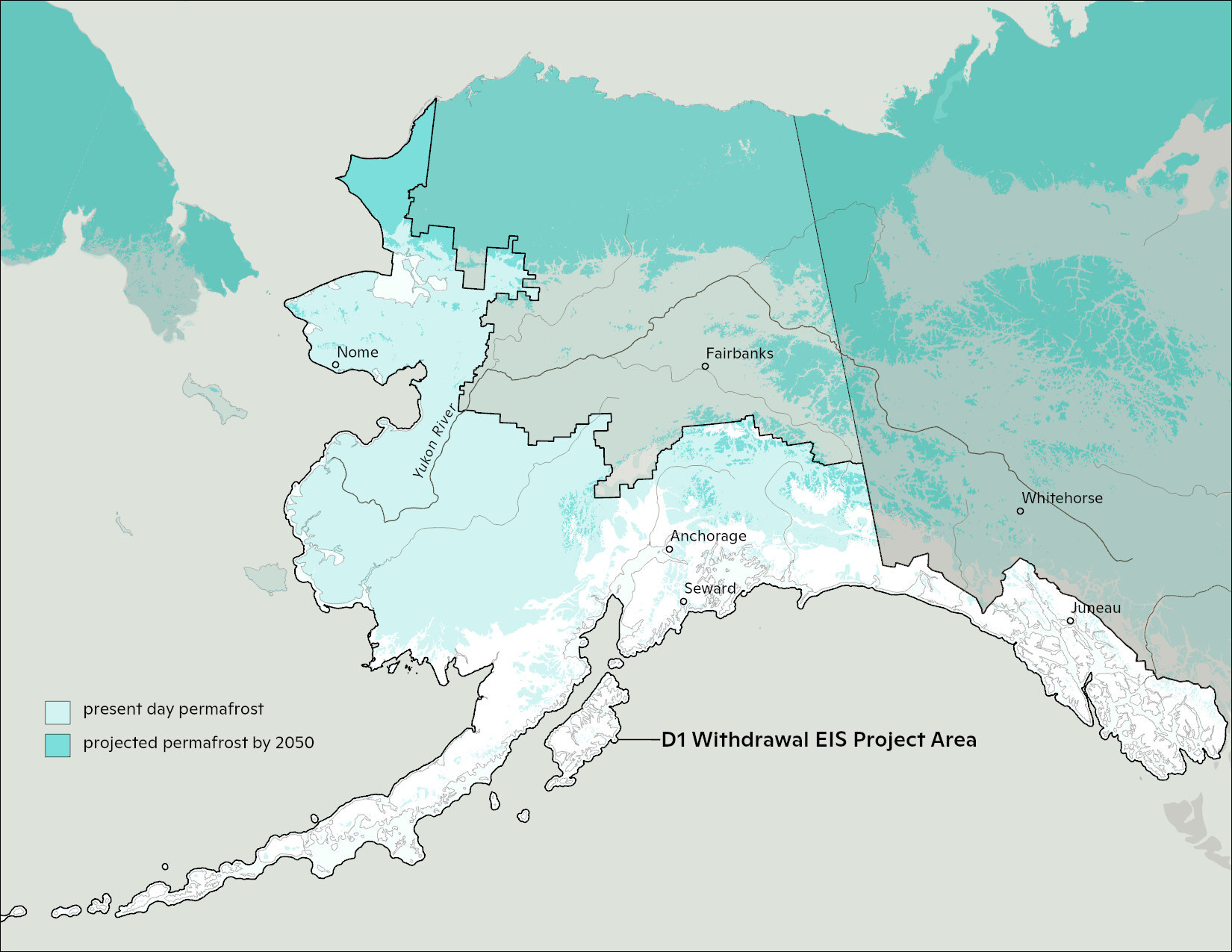

A map representing the overlap of D-1 lands and permafrost in Alaska — much of which is projected to disappear by 2050.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

For example, in 2023, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) proposed to open nearly 28 million acres of protected lands (known as D1 lands) across Alaska to industrial leasing—a move that would threaten the health of the surrounding environment and the many communities that rely on it. Permafrost Pathways and other opposed groups used maps to highlight how D1 lands overlapped with culturally significant subsistence hunting and fishing grounds, animal migration routes, and permafrost, all of which would be threatened. Alaska Native communities also cited concern for the unprecedented risks to traditional lifeways in the greater Yukon-Kuskokwim region, an area already under immense pressure due to climate-fueled disturbances like permafrost thaw and flooding.

Following public input on the environmental impacts of this decision, BLM issued a final environmental impact statement. With the help of maps and overwhelming public opposition to the proposed withdrawal, BLM ultimately left protections for D1 lands intact, marking a victory for both the environment and surrounding communities.

Mapping Our Places: Voices from the Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative, published by the Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative detailing Indigenous mapping projects in communities in Alaska, northern New Mexico, Montana, and the Hawaiian island of Kaua’i.

Photos by Tiffany Windholz / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Reclaiming the past for a more equitable Arctic future

Permafrost Pathways’ GIS capacity-building work contributes to a larger, global effort to decolonize place and space by empowering Indigenous mapmakers.

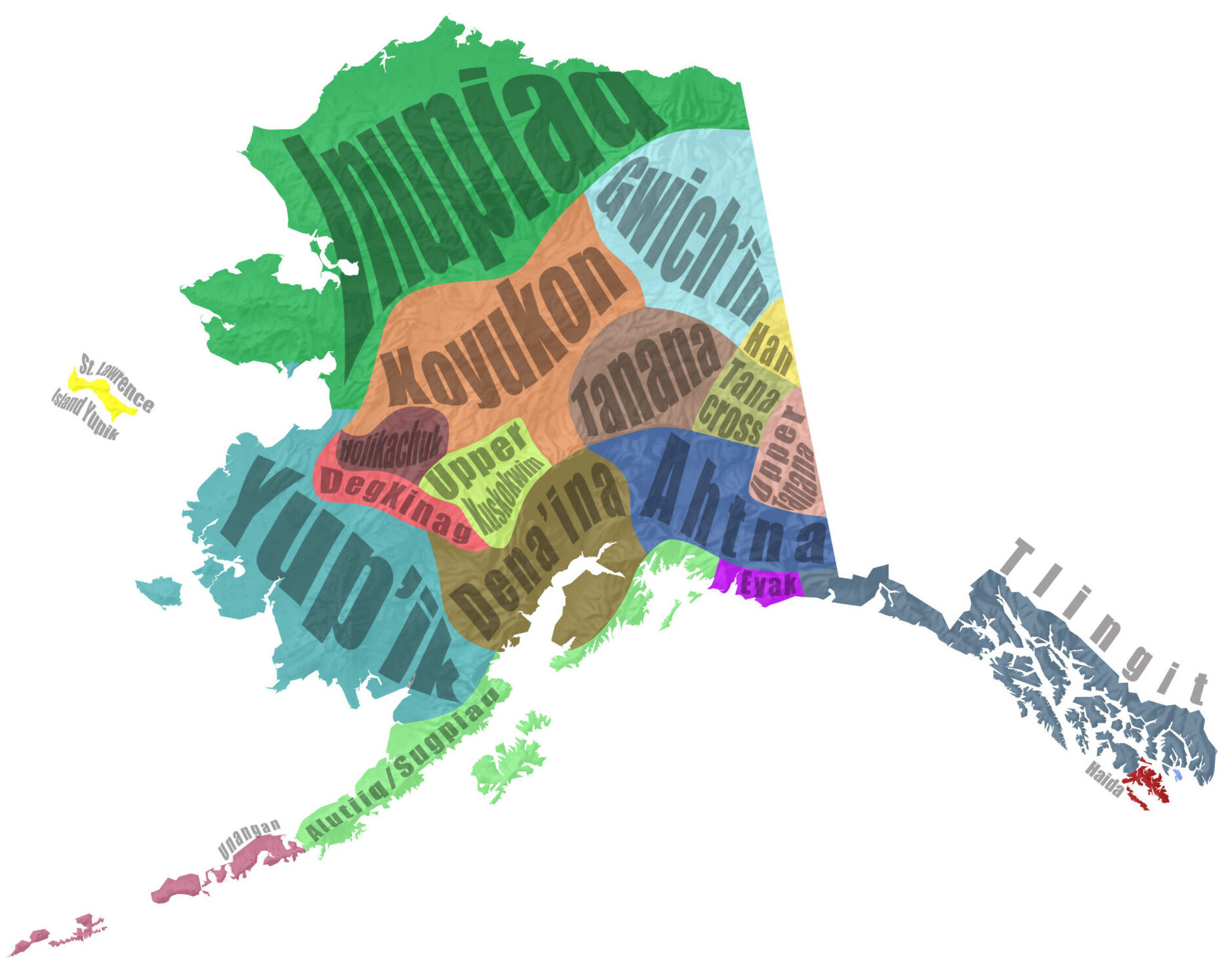

For Alaska Native communities, Indigenizing the map is a way to reclaim ancestral homelands, one traditional name at a time. It’s also a way for future generations to maintain their cultural heritage and connection to place through their Native languages.

Alaska Native languages and cultures.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“I personally would love to see more of our Tribes speaking their traditional languages. Reclaiming language is one of the most powerful things we can do as Native peoples. There is so much that’s been lost, and language plays a huge part in that. There is so much traditional knowledge that doesn’t directly translate to English. Traditional place names, traditional hunting grounds, subsistence trails, I mean the list goes on,” Peter said.

Darcy Peter and Nelson Lagoon’s Angela Johnson discussing environmental change happening in the community.

Photo by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Supporting this global movement means removing access barriers to GIS education and tools for Indigenous communities. For Permafrost Pathways, Peter says the overall priority of GIS capacity-building is “to uplift Tribal capacity and Tribal sovereignty.” With the help of powerful allies like Esri, the project is moving that needle.

“For each respective Tribe to have a mapmaker in their community that speaks their traditional language, and for communities to be their own GIS experts, their own scientists, their own advocates, their own storytellers, their own decision-makers—that would be one of the biggest successes of the project, and quite frankly of my life.”

Go to top